SAN MARCOS, TEXAS — Kristy Money and her husband, Rolf Straubhaar, had lived all over the world before they settled down into two teaching positions at Texas State University.

“We wanted an old house near the school, and when we found this one, we were so excited,” says Kristy, a clinical psychologist and psychology professor. “A big part of buying and fixing up a historical home is learning all about it. In doing our research, that’s how we found out about the ‘Z.’”

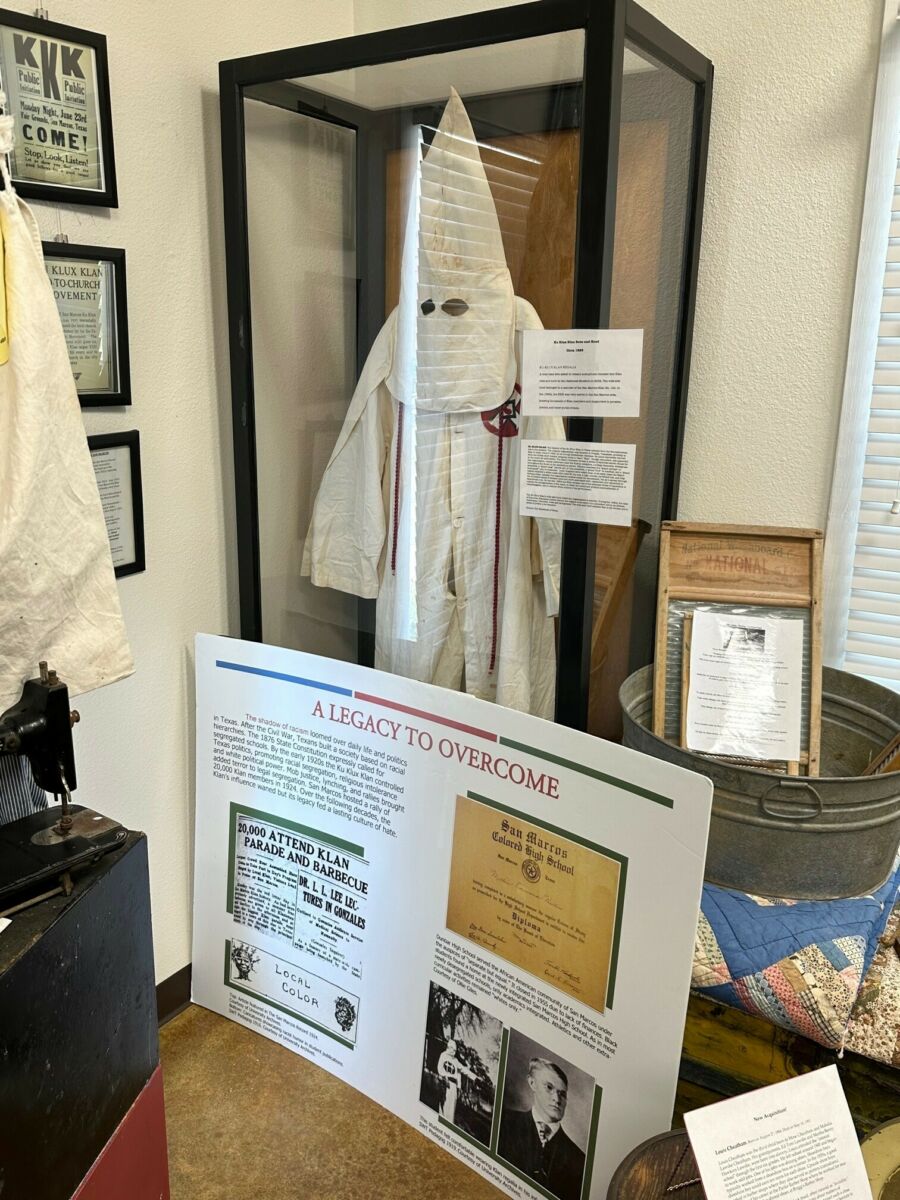

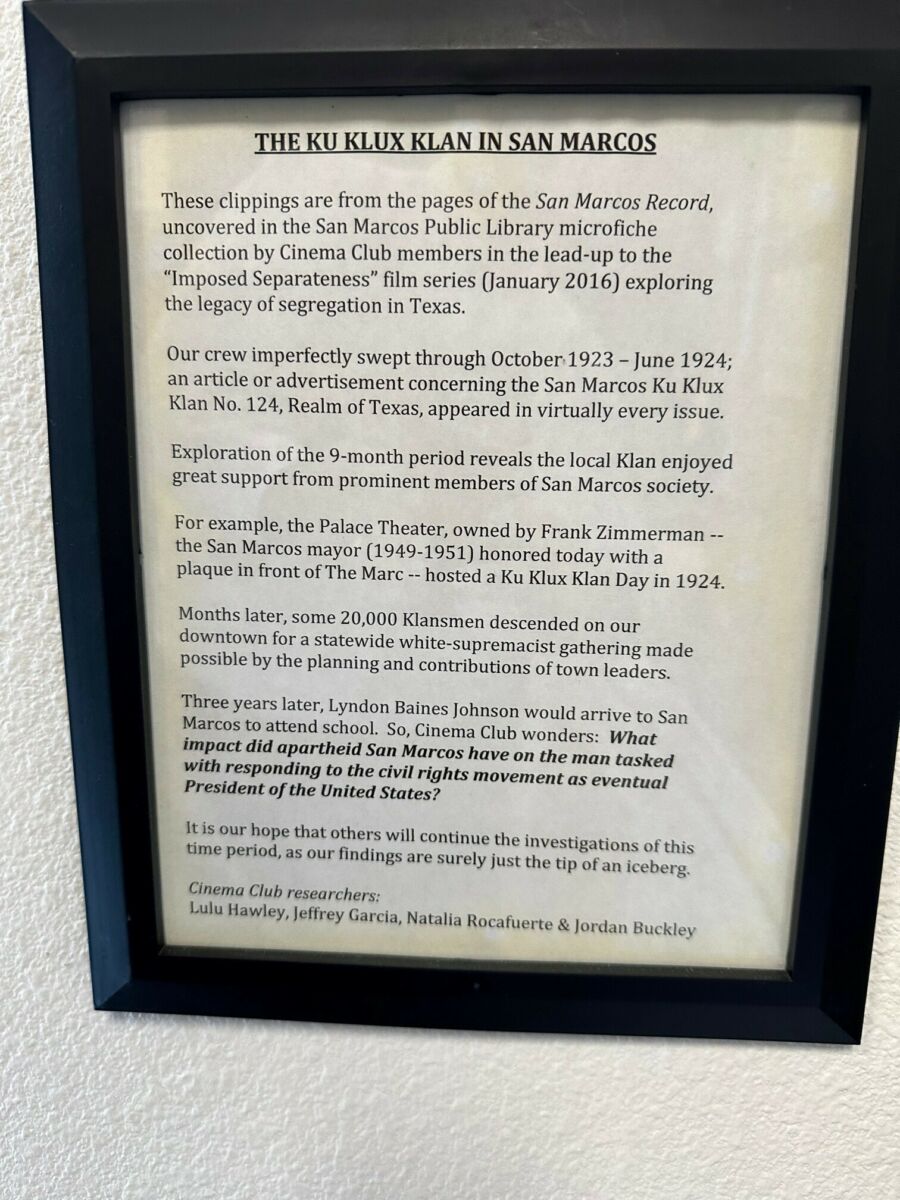

An ornamental ironwork initial adorns a small Juliet balcony at the house’s attic level. Now mostly hidden by tree limbs, the Z is still an issue — because of what it symbolizes. The house was built by a former San Marcos mayor, Frank Zimmerman. Zimmerman had ties to the Ku Klux Klan and even hosted Klan rallies and screenings of the film “The Birth of a Nation” at his theater in the 1920s.

But when the couple went to the San Marcos Historic Preservation Commission for a permit to remove the symbol, they were denied. Now, Kristy and Rolf are suing the city of San Marcos and the commission.

“Our home should be a reflection of who we are as a family,” Kristy explains. “And that means doing everything we can to fight racism in all its forms. These are the values we want to leave our children. This is a fight for our property rights, and our children are watching.”

Kristy and Rolf are being represented by my colleagues at the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Center for the American Future. In Texas, cities are limited in what they can regulate. Mostly that means nuisances and safety hazards. But San Marcos’ HPC has gone far beyond that — regulating the facades of structures within the district.

And while Kristy and Rolf live in that historic district, their home itself doesn’t enjoy that designation. The couple applied for a historic marker for the house. But the home is neither old enough nor architecturally unique enough to warrant such a marker, they were told.

Still, the HPC claims it has the authority to force the family to keep displaying that troubling Z.

“That’s the whole point of being in a historic district, you know, to kind of like respect the past,” one commission member told the couple.

“I like the idea of a historic preservation commission as a point of reference,” says Rolf, an education professor. “It’s so unfortunate that here, the commissioner has become a de facto homeowners association for this part of town. It’s a way for people to enforce their own aesthetics on other people.”

This has been an emotional battle for the family, and many in the neighborhood are taking sides.

“For me, a home is a place for me and my kids and wife to feel safe, to be ourselves,” Rolf explains. “It’s a reflection of ourselves, an expression of our values. We have no issue with telling the history of Mr. Zimmerman; we’d love for it to be a teaching moment. But I don’t want anyone associating my values with Mr. Zimmerman.”

Kristy agrees.

“Property rights are human rights, and anti-racism is worth fighting for, no matter how uncomfortable or unpopular that might make us,” she says.

It’s time to put cities, and particularly unelected bureaucrats, back in their constitutionally defined box so that people can live their lives. That’s all that Kristy and Rolf want.

“The ideal outcome for me would be for us to live our lives without that existential dread that the historic commission has been causing,” Rolf says. “Without worrying about and prepping for another committee meeting, or worrying what pretext they’ll use next. It takes up time and energy we’d rather be spending with our kids and living our lives.”