KINGSVILLE—The story of Texas is a story of adaption and resilience. The only alternative, really, is death. Nowhere is that more clear than here on the iconic King Ranch, with its 825,000 acres of inhospitality, patches of impassible scrub, and a dry vastness that calls for every ounce of Texas grit and ingenuity to overcome.

KINGSVILLE—The story of Texas is a story of adaption and resilience. The only alternative, really, is death. Nowhere is that more clear than here on the iconic King Ranch, with its 825,000 acres of inhospitality, patches of impassible scrub, and a dry vastness that calls for every ounce of Texas grit and ingenuity to overcome.

That hasn’t changed over the years. King Ranch has always been about overcoming seemingly insurmountable obstacles. And it faces new challenges now, including waves of migrants sent north by Mexican criminal cartels. But more on that later.

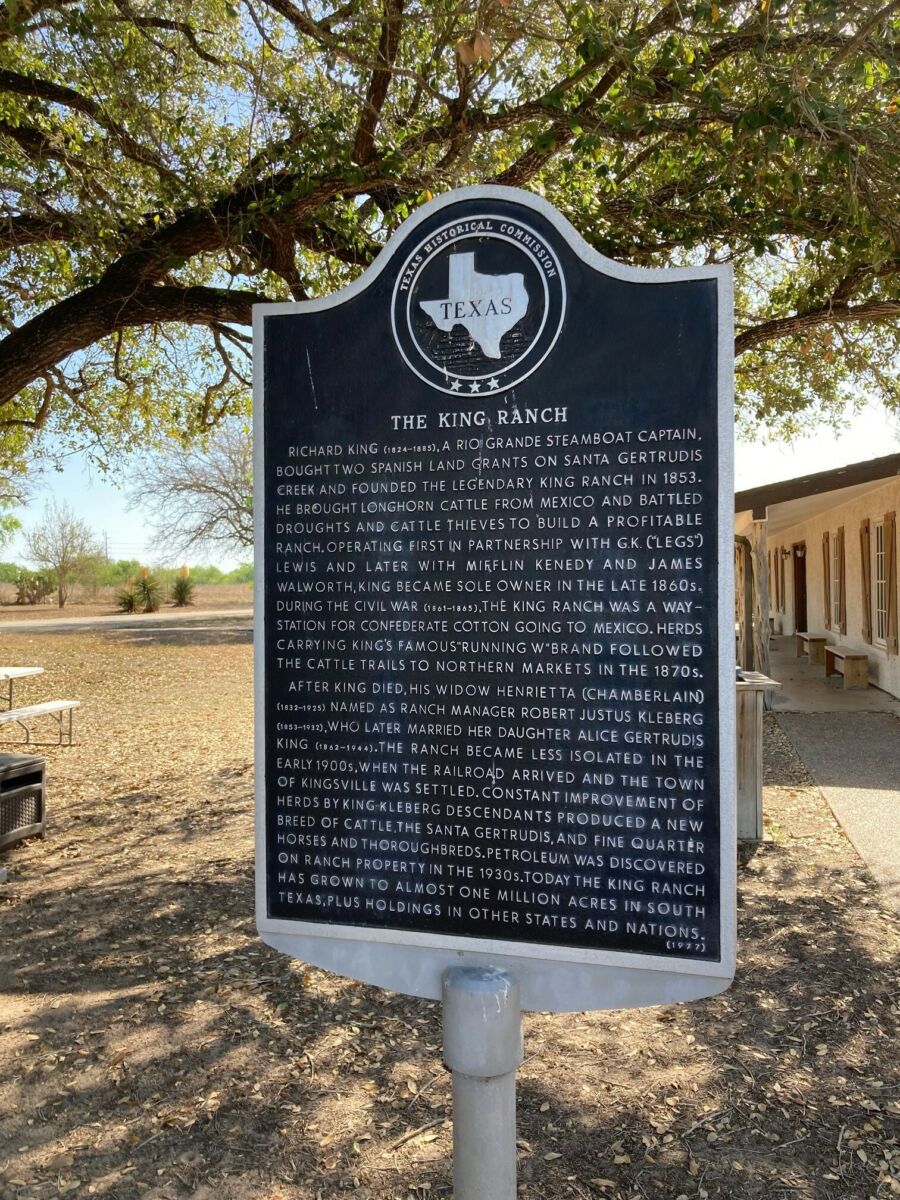

The struggle to survive and thrive is a defining trait of Texas and Texans, as TPPF’s Josh Treviño eloquently explains. It’s certainly part of the story of Captain Richard King, a riverboat pilot who founded the ranch at the site of Santa Gertrudis Creek—the only surface water for miles and miles—in 1852. He discovered the creek as he traveled from his port of Brownsville to Corpus Christi for a fair. In Corpus, he met with a friend, Texas Rangers Capt. Gideon Lewis—and they decided to build a ranch on the site of that creek.

King purchased the Rincón de Santa Gertrudis, an old Spanish land grant, from the Mendiola family. The 15,500 acres cost $300. Other land purchases followed, and at its largest, the ranch included 1.2 million acres. When Lewis died (killed by the angry husband of a woman he was seeing), King brought in more partners, but he retained operational control of the ranch for the rest of his life.

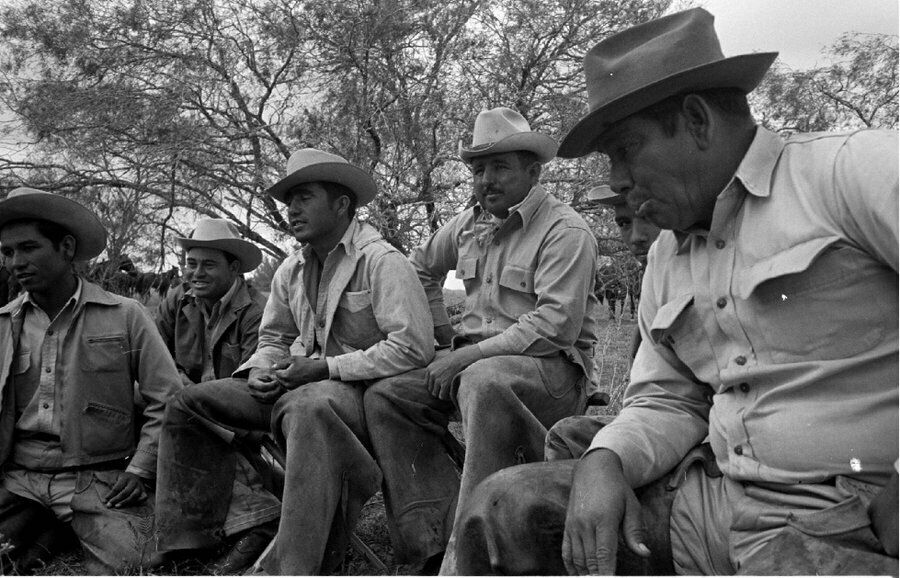

He had the land, but he needed more cattle. In 1854, as a drought ravaged South Texas and northern Mexico, King rode to the village of Cruillas in the Mexican state of Tamaulipas. He offered to buy the town’s whole herd. The townspeople agreed, knowing that every head of cattle would die in the drought if they did nothing. But King realized he was driving the town’s livelihood north—along with their prospects. He returned to Cruillas and made the people an offer: If they would come to King Ranch and work for him, he would ensure they would be fed and paid a good wage. They readily agreed—and became known as Los Kineños, or King’s Men. Many of their descendants still work the ranch. And the King family built homes, a school, a church, a general store for their workers.

“Adapt or die” also explains one of the King Ranch’s other success stories. Texas Longhorns are tough creatures, uniquely suited to the vast, dry wastes of South Texas. But they weren’t as profitable as other breeds, such as Herefords, because of the leanness of their meat (tallow, made from rendered beef fat, was highly valuable). So two of King’s heirs, Dick Kleberg and Robert Kleberg Jr., began a breeding program to produce a more marketable variety that could survive the harsh conditions of the ranch. By combining heat-resistant Indian Brahmans with meatier British Shorthorns, the Santa Gertrudis breed was developed. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recognized it in 1940 as the first new American breed of cattle.

King Ranch adapted many things; in the South Texas region that was once referred to as the Wild Horse Desert, Richard King began breeding a line of horses that would soon become the Quarter Horses we know today. Ranch lore says that Old Sorrel, bought as a colt by King’s grandson, became the sire to champions—including the first American Quarter Horse Association Grand Champion in 1941.

But Thoroughbreds were also an interest of Richard King’s descendants. The first Thoroughbred brought to the ranch in 1934 was Chicaro; he was brought to improve the Quarter Horse breeding program. More Thoroughbreds were added, and King Ranch soon bought Bold Venture, the winner of the 1936 Kentucky Derby. He sired more winners with King Ranch mares—including Assault, the ranch’s most famous racer, who won the Triple Crown in 1946. Assault is still remembered with a memorial at the ranch, where his hooves, head and heart are buried (as is traditional for Thoroughbreds).

With any ranch—with any human endeavor—there are ups and downs, successes and failures. There are booms (King Ranch leased some of its land to Humble Oil in 1933) and busts.

But there are new challenges. In August of 2021, an overloaded van carrying 29 migrants and a driver crashed on U.S. 281. The driver was speeding and attempting to veer off the road. He might have believed he was being pursued—but he wasn’t. Yet his top-heavy passenger van flipped, hitting a utility pole and a stop sign. In all, 11 people died in the crash—and every other passenger suffered critical injuries.

But there are new challenges. In August of 2021, an overloaded van carrying 29 migrants and a driver crashed on U.S. 281. The driver was speeding and attempting to veer off the road. He might have believed he was being pursued—but he wasn’t. Yet his top-heavy passenger van flipped, hitting a utility pole and a stop sign. In all, 11 people died in the crash—and every other passenger suffered critical injuries.

“A surge in migrants crossing the border illegally has brought about an uptick in the number of crashes involving vehicles jammed with migrants who pay large amounts to be smuggled into the country,” local news station ABC 13 reports. “The Dallas Morning News has reported that the recruitment of young drivers for the smuggling runs, combined with excessive speed and reckless driving by those youths, have led to horrific crashes.

Many of these crashes occur on highways like 281 that cut through King Ranch. But it’s not just migrants being transported in vehicles. Many attempt to walk through the unforgiving vastness. Far too many die along the way, and often, they’re discovered by ranch workers.

TPPF’s Ken Oliver has written about this aspect of the border crisis, worsened by the Biden administration’s actions—and inactions. And he’s covered how the crisis has impacted King Ranch.

But to gain a broader understanding of how this Texas institution and Texas itself are being affected, it’s important to know a little more about King Ranch—and how it personifies that central tenet of Texas: adapt or die.