Consider Sinaloa. If you don’t know Sinaloa, you ought to know it is physically beautiful and possesses a rich local culture. It is also a historic and current epicenter of cartel activity: the homeland of the infamous “El Chapo.” He is now a permanent guest of the United States government at a maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado, but his family remains in Sinaloa — and they remain in the family business.

Over two years back, in October 2019, Mexico’s Guardia Nacional attempted to arrest one of them: El Chapo’s son Ovidio. The son, then 29, more than deserved arrest. Known as “El Ratón,” he inherited his father’s operation and his status as one of the world’s most-wanted criminals. The Guardia Nacional struck, and got their man — but the Sinaloan cartel struck back, effectively besieging the Guardia Nacional team with their prisoner, and not incidentally overrunning the city center of Sinaloa’s capital Culiacán. For several tense hours, Mexico faced the reality of a criminal cartel — with light infantry and homemade armored vehicles in the streets — seizing and holding a major-state capital city. It would be the functional equivalent of the Mafia seizing control of Austin, or Tallahassee, or Sacramento, except the Mafia respects the power of the state and historically tries to avoid provoking it. There is no such respect in Mexico.

The crisis ended with the intervention of Mexico’s President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador — popularly known as AMLO — who commanded his men to release El Ratón. It was, he said, an attempt to avoid further violence. Accept that explanation or not as you will: it is the logic of appeasement at best. But perhaps it’s something else. At the time, commenting on it to a friend who understands Mexico very well, he pointed out that I missed the larger story and its continuity. AMLO’s acquiescence to the Sinaloan cartel didn’t start with the capitulation in the October 2019 battle of Culiacán. Even in his presidential campaign in 2018, AMLO was seen to avoid criticizing the Sinaloans — or even to obliquely praise them. There is something there, my friend, that demands explanation.

Five months later, in March 2020, video emerged on social media of a meeting between AMLO, El Chapo’s mother, and El Chapo’s lawyer. The video was taken on a road, newly constructed by the Mexican government, to service the remote hamlet of Badiraguato — where the aged matriarch lives. It was a curious meeting, the President of Mexico paying respects to the mother of one of the greatest criminals of the modern era, and his counsel. Questioned about it after the video’s emergence, AMLO defended himself: how could he refuse an elderly woman’s desire to meet him? “I am not a robot,” said AMLO, “I have feelings.”

Some time back, I asked a Mexican state official about these very strange interactions between the President of Mexico and the Sinaloan cartel. He said directly: “The President has an alliance with the cartel.” An alliance? “Yes of course,” he replied, as if I was a fool not to see it. I do see it. But I am looking for other explanations.

Sinaloa, for some time, has had a government run by PRI — the old autocratic party that more or less ran Mexico with an iron hand from the 1920s through 2000. But AMLO’s party coalition is MORENA, a Spanish acronym that is less interesting for its constituent words than for the acronym itself. La Morena, you see, is the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Queen of the Americas, who appeared to Saint Juan Diego Cuāuhtlahtoātzin on December 9th, 1531, and — if you believe in this sort of thing — spurred the genuine conversion of the surviving Aztecs to Christianity. (In the spirit of full disclosure, I do believe in this sort of thing: I’ve participated in the pilgrimage to her basilica on her feast day of December 12th five times across the past ten years.) MORENA, the political party, is neither Catholic nor Christian — that isn’t the purpose of invoking her name in theirs — but it is interested in asserting itself as authentically Mexican. It is a left-populist movement that, unlike leftist movements of the past, does not shy away from cultural signifiers. It understands that La Morena is the font of a particular sort of Mexican-ness. Thus the name.

Sinaloa had a government run by PRI, but AMLO wished for a government run by MORENA. This is where matters become somewhat opaque. Here’s what’s on the record: on June 6th, 2021, there were elections across Mexico, including in Sinaloa. Before June 6th, Sinaloa was controlled by PRI. After June 6th, Sinaloa was controlled by MORENA.

You may ask yourself: so what? Well, what if I told you that just prior to election day in Sinaloa, the Sinaloan Cartel deployed its full might across the state, fanned out into every municipality — and kidnapped hundreds of election workers from PRI, PAN, and every other party except MORENA? What if I told you that these hundreds of hostages — get-out-the-vote workers, phone bankers, pollsters, poll watchers, elections officials, and beyond — were held in secure locations across Sinaloa, deprived of all outside contact, and then released unharmed after the polls closed? What if I told you that because of this extraordinary cartel action, MORENA was the only party in Sinaloa with an election apparatus in the field on election day, and therefore won?

If I told you all that, it certainly would put the Mexican President’s obsequious behavior toward the Sinaloan cartel and its ruling family in a new light, wouldn’t it?

I could tell you all that — but I couldn’t prove it. The man in Mexico City who told me this tale — a credible man, a genuine Mexican patriot — also can’t prove it. You see, of the hundreds of (allegedly!) kidnapped election workers across Sinaloa, exactly none are willing to go on the record. Not one. Not a single one.

This is the quality of conversations in Mexico City now: a dreamland experienced in fever, allusion, and possibility layered upon an inadequate veneer of known fact.

What we found there — three of us, all from the Texas Public Policy Foundation — was simultaneously enriching and disturbing. It was enriching in the sense that we understood a bit more of what’s underway in Mexico. It is impossible to do the things we do professionally — craft and advocate for policies on immigration and border security — without that understanding. Engaging strictly on the American side is tactical and operational work. Engaging on both the American and Mexican sides is strategic work. The question for us is whether the Mexico-side engagement would involve a partner or not. That’s no small matter: for the past century, the governing assumption in US-Mexico relations has been that there is a peer, sovereign-state partner south of the Rio Grande. For most of the past century, that assumption has been valid.

It may not be valid any longer. I do not mean that there is no Mexican state. There quite obviously is. But that state is manifestly no longer the only entity exercising sovereignty in Mexico. Former United States Ambassador to Mexico Christopher Landau, this past April, stated openly that criminal cartels control, in his estimation, 35% to 40% of Mexican territory. The remarks spurred a firestorm of denunciation in Mexico — the diplomatic norm is to pretend all is well — but everyone knew it was true. It’s still true. Every year, that percentage goes up. At some point, there is a critical mass reached — no one knows exactly where it is — and the true sovereign power in the country shifts elsewhere.

There is a tendency to assume this doesn’t affect us, here in Texas, here in the United States, comfortable and unfamiliar with names like Culiacán, Ayotzinapa, or El Mencho. But it does. Among our foreign challenges, only that from the Communist Party of China constitutes a comparable threat. That’s because of the domestic corruption the Chinese Communists wreak — ask LeBron James about genocide in Xinjiang sometime — but the domestic corruption Mexican criminal syndicates bring is easily as grave. Some years back, south Texans were shocked to learn that the Hidalgo County, Texas, sheriff’s department was subcontracting itself out to Los Zetas. That wasn’t even remotely unprecedented: some years earlier, the sheriff of Cameron County, Texas, was known to be in league with the Gulf Cartel. His popular nickname: “Protect the Load” Cantu.

Some weeks back, I had lunch with a woman with extensive experience in Mexican affairs. We discussed my grandfather’s hometown of Roma, Texas. I told her about the time I sat on the bluffs at Roma, overlooking Ciudad Aleman on the Mexican side, and listened to a gun battle underway south of the river. She told me about the time she was on the river just south of that spot, chatting with a Border Patrolman. He had to move on, and he told her she should move on too. He did, and she didn’t. Shortly a teenager clambered across the shallow river, demanding to know who she was and what she was doing. I’m an American on American soil, she said. Yeah okay, said the teenager, but you’re also alone and we need to get across. It’s time for you to go. She went.

Some weeks back, I had lunch with a woman with extensive experience in Mexican affairs. We discussed my grandfather’s hometown of Roma, Texas. I told her about the time I sat on the bluffs at Roma, overlooking Ciudad Aleman on the Mexican side, and listened to a gun battle underway south of the river. She told me about the time she was on the river just south of that spot, chatting with a Border Patrolman. He had to move on, and he told her she should move on too. He did, and she didn’t. Shortly a teenager clambered across the shallow river, demanding to know who she was and what she was doing. I’m an American on American soil, she said. Yeah okay, said the teenager, but you’re also alone and we need to get across. It’s time for you to go. She went.

All this can get much worse. As things are proceeding in Mexico, it will.

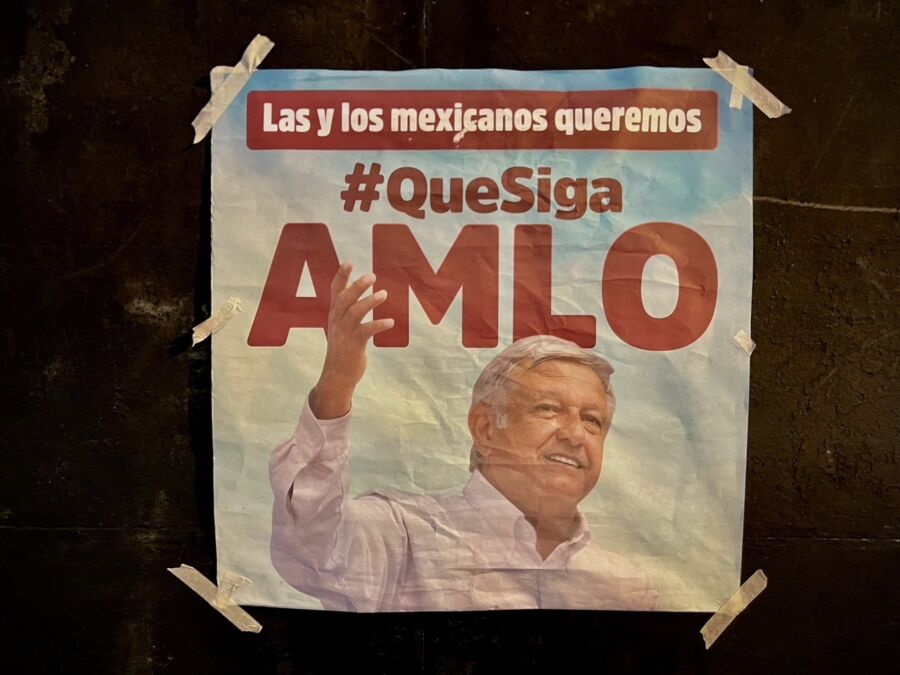

All this takes place against a strange backdrop of a left-populist authoritarianism that descends by stages across Mexican governance. AMLO and MORENA are genuinely popular, if you believe polls and election outcomes reinforced by cartel gunmen. He is a messianic figure, seized with a surpassing belief in himself. In 2006, after narrowly losing that Presidential election, he simply staged a sham inauguration and had his followers occupy the center of Mexico City — which the legitimate government wisely waited out, and allowed to gradually dissipate. Now he holds the reins of power, and he consolidates them with alacrity. State governments, once significant centers of power in Mexico, are stripped of their fiscal independence. Buildings across Mexico City are plastered with cult-of-personality posters featuring AMLO’s shining visage, and the slogan — in translation — WE MEXICANS WANT AMLO TO CONTINUE.

Across multiple conversations, we hear again and again that the Mexican Army is increasingly the instrument of AMLO’s governance. The Army runs the airport, the Army is in charge of the major construction projects, the Army is the institution of first resort in getting things done. The Army is doing everything except, it seems, fighting the cartels. At one of the major thoroughfares into Mexico City’s historic El Centro, there is a protest encampment. “Indigenes,” spits a taxi driver in contempt. They certainly have all the qualities of Mexico’s indigenous communities: a particular look, a particular dress, and enduring a particular contempt from Mexico’s ruling class. The encampment is festooned with gruesome images of what look to be wounds from torture. I ask a woman there what all this is for. She tells me they are from Tierra Blanca, a hamlet in the Oaxacan highlands. There is a criminal gang there that is extorting them, ruling them, and torturing and killing them when they resist. They want the Army to defend them. That’s all they want, she says. The Mexican Army should fight for Mexicans.

It’s a good theory.

Let’s not single out the Army. There is also the Instituto Nacional de Migración, the Mexican-federal agency that is supposed to oversee the welfare of the many migrants from, and transiting through, Mexico en route to the United States. The INM is, according to multiple individuals with whom we spoke, a human-trafficking cartel all its own now. One scholar told us that it goes “all the way to the top.” An activist told us that migrants who make it to the US-Mexico border now pay off three parties: the local cartel, the (actual, legitimate) Mexican tax authorities, and INM. Still another activist told us of a particularly horrific arrangement between the INM and the Guardia Nacional on a particular section of the border: in exchange for the Guardia Nacional acting as INM’s enforcer there, the guardsmen are allowed to rape their pick of the migrant women passing through.

I could tell you more. There is much more. But I think this is enough.

Mexico City is one of the great treasures of the world, with seven hundred years of history, surrounded by an additional thousand years of antiquity: the stunning pyramids of Teotihuacan, just a short day trip from the metropolis, are contemporaneous with the height of the Roman Empire. The city is teeming, energetic, shocking, and alive in ways you rarely see in an American context. It embraces jewels of the Spanish Baroque, with some of the most grand and glittering alters in any church, anywhere. It sports treasures of the lost world of the Aztecs, an occasional stone idol’s head peeking forth as the foundation of some Spanish-era building.

Mexico City is one of the great treasures of the world, with seven hundred years of history, surrounded by an additional thousand years of antiquity: the stunning pyramids of Teotihuacan, just a short day trip from the metropolis, are contemporaneous with the height of the Roman Empire. The city is teeming, energetic, shocking, and alive in ways you rarely see in an American context. It embraces jewels of the Spanish Baroque, with some of the most grand and glittering alters in any church, anywhere. It sports treasures of the lost world of the Aztecs, an occasional stone idol’s head peeking forth as the foundation of some Spanish-era building.

It harbors some of the best Art Deco and modernist masterpieces anywhere. It is the kind of place where you take a coffee with choriqueso in an eighteenth-century enclosure — and then retire to the restroom, where you find an Orozco mural at the entrance. It is a city where you see genuine faith in God and His promises that vanished from the American mainstream with the rise of the ruling sophisticates. It is a city where you discover a whole half-mile of antiquarian bookstores, each a treasure house, and lose your afternoon to their exploration. It is a city where, were I twenty years younger and with no family, I might spend a few years.

There is much to love in Ciudad México — and in Mexico at large. Half of my ancestry is here. There are elements to it, especially in the tales of the conquistadors and the original Zapatistas, that spur in me great pride.

But the Mexican state does not seem to live up its inheritance. Mexicans now tell us of a supposed coming era of military rule, of increasing cartel-ization of the country, of an inexorable slide into the rule of the strong. Americans want, and ought to want, a Mexico that is fully sovereign over itself. For some reason, the Mexican state now seems disinterested in that. I asked yet another friend about this curious intersection, the seeming contrast between the left-populism of AMLO and the strange acceptance of rival sovereignties emerging across the country. He thought about it a moment, and said: Mexico is what happens when a great country has an elite that simply does not care about it.

Be it so. It is not for us to save Mexico. But it is for us to defend ourselves — preferably with Mexican partners, but without if need be. That is ultimately their choice. The decision to act is ours.

Joshua Treviño — From Ciudad México, December 2021.