This commentary originally appeared in Forbes on August 12, 2015.

Almost one-third of California households, 31 percent, can’t meet their basic costs of living, this, according to a United Ways of California report issued last month entitled, “Struggling to Get By—The Real Cost Measure in California 2015.”

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, California’s official poverty rate, as averaged from 2009 to 2013, was 15.9 percent. So, why the big difference? Is the Census Bureau wrong? Is the United Ways report overly alarmist?

The fact is that the nation’s official poverty measure is sorely lacking. Its biggest weakness is that it does not account for regional cost of living variances. As far as the official poverty rate is concerned, the cost of living in New York City or San Francisco is the same as it is in Houston or Kansas City.

Further, the official poverty rate only accounts for cash assistance in determining household income. As such, it ignores the value of food assistance (the Electronic Benefit Transfer card spends the same as cash at the grocery store, but, the official poverty rate doesn’t count it) as well as rental subsidies in addition to other benefits and costs.

The Census Bureau developed an alternative poverty measure to address the shortcomings of its half-century-old traditional poverty yardstick. Known as the Supplemental Poverty Measure, it shows that California has the nation’s highest poverty rate, 23.4 percent.

But, while showing a higher poverty rate for California than the old, official measure, the Supplemental Poverty Measure still indicates a lower rate of poverty than does the study from United Ways of California. The difference is likely due to the fact that the Census Bureau only looked at state-to-state housing costs while the United Ways researchers included a far larger basket of goods and services—all of which cost more in California than in America at large.

In a section of policy recommendations, United Ways’ report suggests ways to address California’s high housing costs. They admit that, “It is not clear what strategies might work best to help struggling households better afford housing” noting that “…low-income housing tax credits and other subsidies for construction of affordable housing have not met the scale of the need…”

But then the report makes a very curious assertion, that “As important as production of new units is, it should be clear that we cannot build our way out of the affordability problem.” This is markedly counterfactual. If the market can’t produce supply to meet demand, then how can we expect prices to fall while meeting demand? A virtually unlimited stream of subsidies can’t solve the housing shortage if new supply can’t be built.

Lastly, United Ways’ authors write that “American taxpayers subsidize home ownership at $3 for every $1 spent to support renters…” This assertion is likely derived from the mortgage interest deduction for homeowners, about $70 billion in 2013, compared to the value of Section 8 housing vouchers, a little more than $19 billion, and the value of government-produced residential housing, about $6.1 billion per year.

There’s a large and obvious missing recommendation from their report, however: addressing the government land-use rules—over-restrictive zoning, environmental blocks, global greenhouse emission considerations, development fees, etc.—that, combined, add 30 to 60 percent to the cost of a new house or apartment, according to a 1997 World Bank study. Other studies verify the role that government restrictions on land use have in creating artificial scarcity in the housing market—try to open a new manufactured housing park in California, for instance.

The average annual value of new U.S. residential housing starts over the first half of 2015 was $364.2 billion. At the low end of the estimate, the cost of overly-burdensome government land use restrictions added some $109 billion, and as much as $218 billion, to the cost of this new construction, putting the American Dream out of reach for millions of people while diverting billions of dollars from being spent on alternative goods and services, such as higher education or health care.

In fact, even the conservative estimate of the added cost of government property restrictions, $109 billion for new private U.S. residential construction, is greater than the combined total of mortgage interest tax deductions ($70 billion), federal rental vouchers ($19 billion) and government-built housing projects ($6 billion). Further, this is only for new housing, it doesn’t include the billions more in inflated costs for existing homes and rent caused by artificial scarcity that prevents new housing supply from meeting demand in California and other states with highly-restrictive rules on property development.

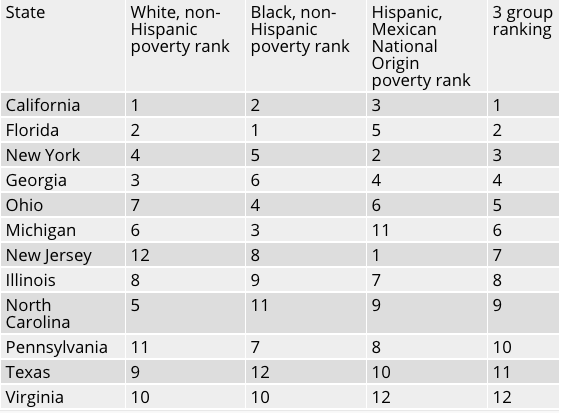

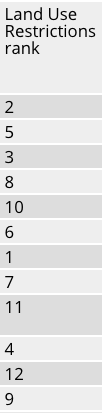

Pulling back and looking at the most-populous dozen states where 60 percent of Americans call home, we can see some trends when it comes to poverty and opportunity. The table below compares the U.S. Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure rankings (2009-2012 averages) among the 12 biggest states for the three largest racial and ethnic/national-origin groups in the nation: White, non-Hispanic; African-American, and Hispanic of Mexican national origin. The last column on the table shows each state’s relative land-use restrictions ranking from a larger study on Freedom in the 50 States.

Land use restrictions don’t appear to have much a correlation with poverty among white, non-Hispanics, but do appear to have a relationship with Mexican-American poverty. This relationship holds up among all 50 states as well.

Advocates for the poor would be well-advised to look first to examining policies that create artificial scarcity in housing markets. As with the ongoing student loan/college tuition fiasco, subsidizing demand with taxpayer money without first allowing supply to increase is only a recipe for a costly, overheated market.

Chuck DeVore is Vice President of National Initiatives at theTexas Public Policy Foundation. He was a California Assemblyman and is a Lt. Colonel in the U.S. Army Retired Reserve.