The Conservative Texas Budget (CTB) limits increases in the state’s two-year appropriations of state funds and all funds (state and federal funds) to less than the average taxpayer’s ability to pay—appropriately measured by population growth plus inflation.

The figure below shows the limits for the currently discussed 2020-21 state budget.

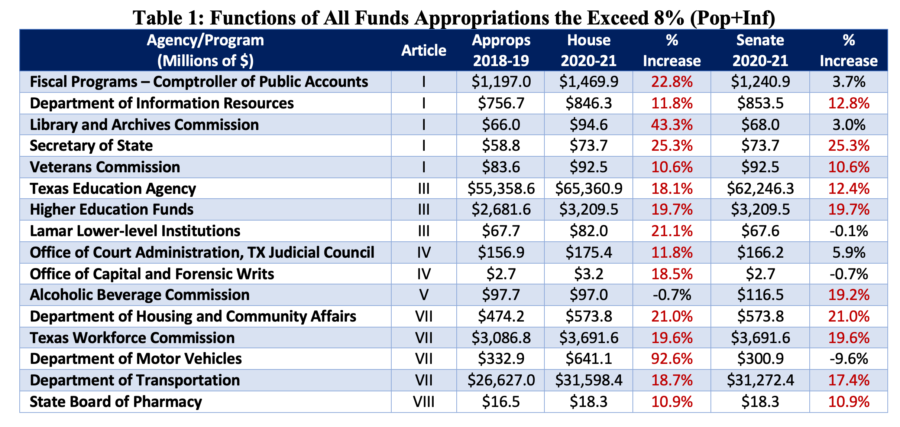

These CTB limits are based on an 8 percent increase in population growth (3.2 percent) plus inflation (4.8 percent) over the last two fiscal years above 2018-19 appropriations for an apples-to-apples comparison. We recently posted a comparison of the Texas House and Senate recommended budgets with the Conservative Texas Budget. Digging into those budgets further, Table 1 lists the state government agencies and programs that exceed the CTB’s growth limit.

At this early stage of the budget process, the total number of functions that may receive appropriations exceeding the CTB growth limit has decreased from 29 in the 2018-19 budget when the growth limit was 4.5 percent to 16 for the 2020-21 budget. This indicates improvement in the potential fiscal responsibility of both chambers. However, both chambers have some work to do to keep their all funds budget amounts below the CTB limit.

The Senate’s budget falls below the CTB limit in state funds, which is mainly because the House allocates $3 billion more toward what could go to public education and property tax relief that shows up in Table 1 under the Texas Education Agency. We exclude the disaster recovery efforts after Hurricane Harvey because these should be an only one-time, unwarranted federal funding amount of $7.1 billion, including $2.5 billion to the Department of Public Safety and $4.6 billion to the General Land Office and Veterans’ Land Board.

The Legislative Budget Board provides explanations for some of these recommended budget increases in Table 1. Here are the LBB’s explanations for a select few of those increases:

- Fiscal Programs—Comptroller of Public Accounts’ budget increases in the House includes $229 million for the Texas Tomorrow Fund but this amount isn’t included in the Senate.

- Department of Information Resources’ budget increases in both chambers “primarily to an estimated increase in consumption of data center services by customer agencies and for providing a full biennium of funding out of Texas.gov receipts for implementation of the Texas.gov state website.”

- Library and Archives Commission’s budget increases by the House primarily because of a $26.6 million one-time increase in Other Funds from the Rainy Day Fund for expanding the State Records Center in Austin, but this amount isn’t included in the Senate.

- Texas Education Agency’s budget increases in the House “attributable primarily to an increase of $9.9 billion in the Foundation School Program (FSP)” while the Senate’s “increase is primarily attributable to increases of $3.7 billion for a classroom teacher salary increase contingent on enactment of legislation, $2.3 billion for property tax relief…”

- Higher Education Funds’ budget increases in both chambers “due primarily to anticipated growth in the value of the Permanent University Fund (PUF) projected by the University of Texas Investment Management Company.”

- Office of Court Administration, Texas Judicial Council’s budget increases in the House by “$3.4 million for Child Protection Courts, increase of $5.0 million to provide a Guardianship Compliance Program…” and in the Senate by $5.0 million for the Guardianship Compliance Program.”

- Alcoholic Beverage Commission’s budget decreases in the House because “of onetime funding during the 2018–19 biennium for Hurricane Harvey assistance and decreases in required information technology funding” and increases in the Senate from “additional funding for law enforcement, including human trafficking investigations and updating the agency’s licensing and tax collection system.”

- Texas Workforce Commission’s budget increases in both chambers are “related primarily to the increase in federal appropriations for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG)”

- Department of Motor Vehicles’ budget increases in the House primarily from an increase of $340.2 million in all funds to administer the driver license program and decreases in the Senate primarily from onetime appropriations for information technology projects and deferred maintenance of buildings and facilities.”

- Department of Transportation’s budget increases in the both chambers by “an estimated $5.1 billion from anticipated state sales tax and motor vehicle sales and rental tax deposits to the State Highway Fund (SHF) (Other Funds) pursuant to Proposition 7, 2015 (an increase of $0.2 billion), an estimated $4.3 billion from oil and natural gas tax-related deposits to the SHF pursuant to Proposition 1, 2014 (increase of $0.9 billion), and all SHF available from traditional transportation tax and fee revenue sources (estimated to be $9.3 billion for the 2020–21 biennium, an increase of $0.7 billion).”

While each of these budget functions that increase by more than the CTB growth limit may be appropriate, they should be watched closely during the budget process for potential inefficiencies as could be identified under a zero-based budgeting approach, which the Senate’s budget had several agencies conduct. Doing so will help assure that the cost of state government doesn’t increase by more than the average taxpayer’s ability to pay to let people prosper.