American employers added 128,000 jobs last month, far above the expected 85,000. In addition, 95,000 more people were hired than initially estimated in August and September. This means that after revisions, monthly nonfarm job gains have averaged 176,000 over the past three months.

These gains were seen in the face of employment declining by 42,000 in the motor vehicles and parts sector due to the recently concluded GM strike. Without the strike activity, manufacturing would have seen a modest increase of 6,000 jobs.

Average hourly earnings for all private nonfarm employees rose by 6 cents to $28.18 for a year-over-year gain of 3%. This is the 15th month in a row that workers have enjoyed year-over-year wage growth at or above 3%, with wages growing faster than the pace of inflation.

There are 4.8 million more Americans working today than before the 2016 presidential election, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

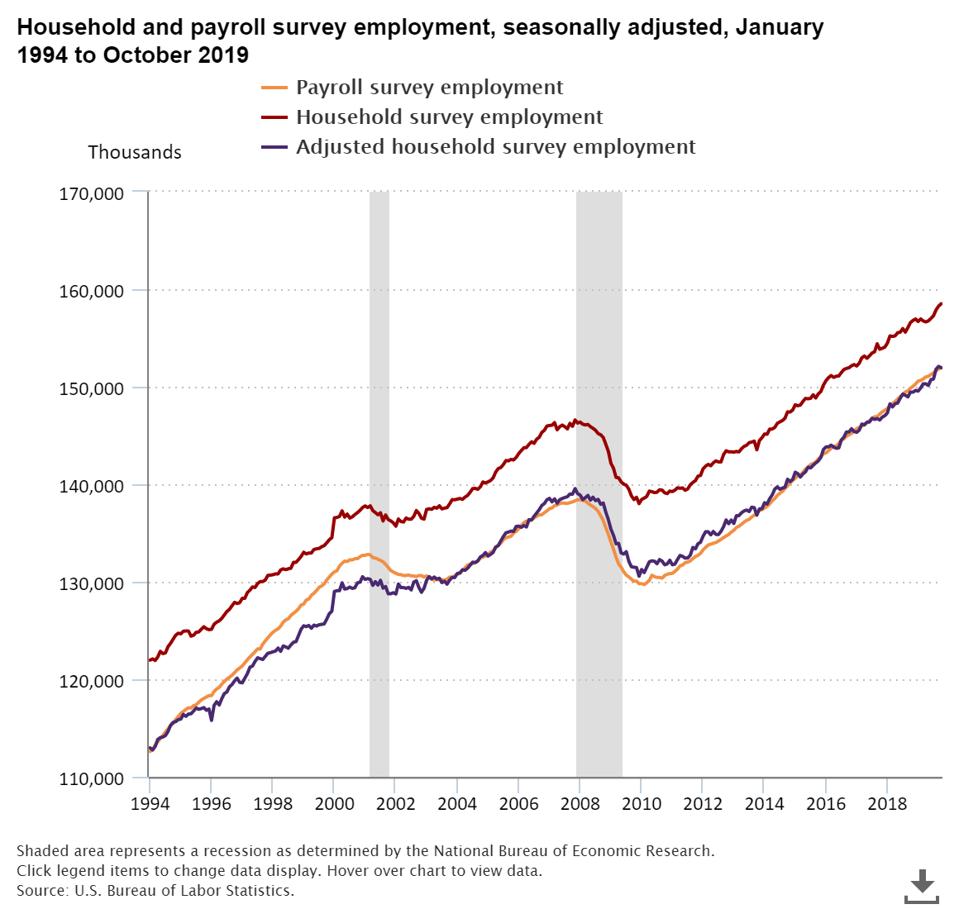

The large upward revisions in the Payroll Survey, a monthly survey sample of 142,000 businesses, was hinted at last month when the Household Survey, which samples 60,000 households per month, showed an employment gain of 391,000 people compared to September’s reported payroll increase of 136,000 (before today’s revision to 180,000). The Household Survey captures people working from home or as independent contractors that the Payroll Survey misses.

The federal government’s jobs benchmark reports, the Household Survey and the Payroll Survey, use … [+]

U.S. BUREAU OF LABOR STATISTICS

But something else might be work here as well, as the national economy continues to adjust to two changes: the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which cut personal and corporate taxes while limiting State and Local Tax (SALT) deductions to $10,000 per filing household; and the ongoing realignment of supply chains due to tariffs and the threat of tariffs on goods from China.

Changes in the federal tax code acted to reduce the implicit federal subsidy for high-tax states, encouraging job-creating capital flows to low-tax states that have resulted in private-sector job growth in the 27 low-tax states, at more than double the rate of their high-tax state counterparts.

Ongoing trade negotiations with the Peoples’ Republic of China may be partly responsible for the slowdown in manufacturing growth in 2019. Structural changes in the broader economy brought on by these factors may result in cumulative employment estimate errors that will eventually result in backward revisions, once the fundamental change in the economy is recognized.

In the case of 2017’s federal tax cut, from December 2017 through September 2019, the 27 low-tax states saw private-sector payrolls increase by 3.90%, more than double the 1.86% growth in the high-tax states.

Some critics of ascribing higher growth in low-tax states to those states’ tax rates, such as Paul Krugman of the New York Times, claim that the warmer weather of the low-tax states or the oil and gas industry in Texas is really the driver. Neither of these factors can fully explain that the six low-tax states adding jobs at the fastest clip since December 2017 are Nevada (negligible oil and gas with a climate that is less appealing than neighboring California); Utah (very small amount of oil and gas); Idaho (no oil and gas and cold weather); Washington (no oil and gas and an infamously rainy climate); Arizona (no oil extraction); and Florida (warm weather, but a tiny amount of oil and gas production).

To test this theory, we can plot the benchmark price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and compare that to the ratio of private-sector jobs created in the low-tax states (of which Texas is the most populous) over the high-tax states on a year-over-year, six-month rolling average. Plotting this (the graphic is at the lead of this article) appears to show some relationship between the price of oil and jobs as Texas weathered the last recession far better than did most states.

But correlation doesn’t necessarily prove causation. Many factors play into employment trends at the state level, with tax rates, regulations, and cost inputs such as land and labor likely playing a greater role in Texas than the price of oil—especially given that Texas’ economy is far more diversified than it was in the 1980s, during a previous oil-bust period.

And, in fact, the apparent linkage between WTI and the large job gains in the low-tax states completely breaks down after the 2017 tax cut, which increased in tax advantage held by the low-tax states over the high-tax states. This fundamental change in the tax law might be affecting the analysis of the national employment numbers, in which case, we may be in for larger employment adjustments in future reports.