This commentary was originally published in the The Federalist on June 18, 2015.

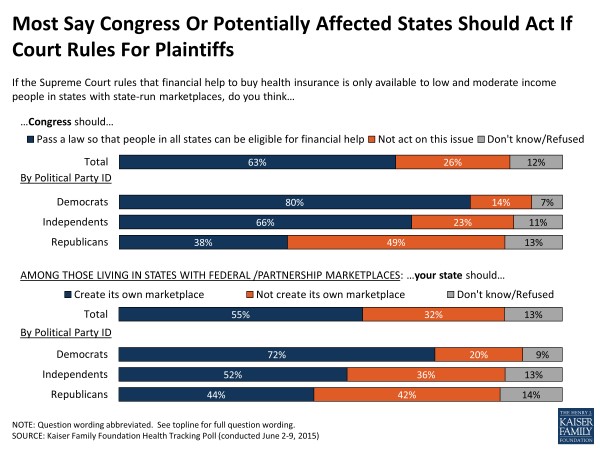

According to a new poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation, 7 in 10 Americans have heard little or nothing about King v. Burwell, the U.S. Supreme Court case that will, any day now, decide the fate of Obamacare’s health insurance subsidies for millions of Americans. Yet 63 percent of those surveyed also say that if the court rules against the government, Congress should act to keep those subsidies in place.

Got that? The vast majority of Americans know almost nothing about this case, but 63 percent have an opinion about what Congress should do in response to a ruling that carries certain policy implications. How can this be?

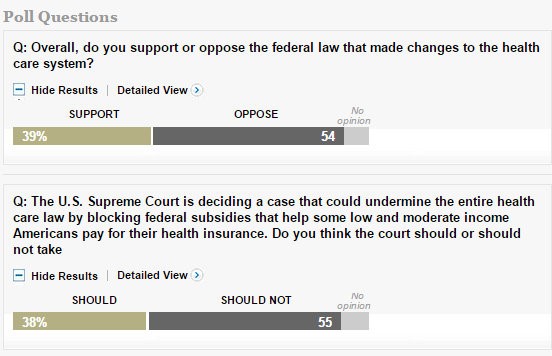

Other recent polls about Burwell and Obamacare also appear to be contradictory, as David Harsanyi noted about the recentWashington Post-ABC News poll, in which the conflicting results stemmed from how pollsters framed the question:

Harsanyi’s response: “Chew over the absurdity and bias of that query (it’s worse when you dig deeper). For starters, it has absolutely nothing to do with the legality or constitutionality of the Obamacare challenge—the reason the case is in the courts. It’s about the theoretical consequences should the court side with the challengers.” In philosophy, this is called petitio principii, the Latin term for the logical fallacy of “begging the question”—when one assumes in the premises the very conclusion one is trying to prove.

Harsanyi’s response: “Chew over the absurdity and bias of that query (it’s worse when you dig deeper). For starters, it has absolutely nothing to do with the legality or constitutionality of the Obamacare challenge—the reason the case is in the courts. It’s about the theoretical consequences should the court side with the challengers.” In philosophy, this is called petitio principii, the Latin term for the logical fallacy of “begging the question”—when one assumes in the premises the very conclusion one is trying to prove.

In this case, the pollsters assume the challengers are seeking to “undermine” the law. In fact, the challengers want the law to be implemented precisely as written—an outcome that would of course result in subsidies only being available on federal exchanges. The challengers claim that’s what the law says and that’s how Congress intended to write it.

We Call This Begging the Question

The challenge against the government rests on the argument that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), acting at the behest of the Obama administration, illegally authorized subsidies on federal exchanges in violation of the plain statutory language of the Affordable Care Act. The law stipulates that subsidies for health coverage under Obamacare must come from “an Exchange established by the State.”

For a variety of reasons, 34 states failed to establish an exchange. The Obama administration didn’t foresee that, but instead of going back to Congress to fix the law, the White House simply ordered the IRS to treat federal exchanges the same as state exchanges. That is, the administration attempted to rule by decree instead of obeying the law.

Any poll question about King v. Burwell that fails to provide that basic context—especially for a public that knows very little about the case—and instead asks about a specific policy outcome is begging the question. The recent Kaiser poll is less egregiously worded, but nevertheless guilty of this same logical fallacy:

The poll offers only one option for Congress should the case go for the challengers—“pass a law so that people in all states can be eligible for financial help”—even though Republicans in Congress are considering multiple responses to Burwell, some of which would extend subsidies, some not.

But instead of asking “if the Supreme Court rules that financial help to buy health insurance is only available to low and moderate income people with state-run marketplaces, do you think…” why not ask a more accurate question: “If the Supreme Court rules that the ACA only allows subsidies on exchanges established by states, do you think…” Then give a range of options, as there are indeed many different things Congress could do besides imposing the White House’s preferred policy outcome.

For example, an estimated 15 million Americans are paying more for coverage on the individual market under Obamacare and not getting subsidies. That’s far more than the 6.4 million now receiving taxpayer help on the federal exchanges. Insurance regulations imposed by the healthcare law—age-rating rules, actuarial-value restrictions, and benefit mandates—have made insurance more expensive, and repealing them would dramatically lower the cost of coverage for everyone, subsidized and unsubsidized alike. Likely, millions of Americans now getting subsidized coverage could afford it on their own if these regulations were repealed.

But the media isn’t really interested in informing the debate with such pernicious facts. That’s why coverage of Burwell has focused almost exclusively on those who might lose subsidies and what congressional Republicans will do about it. The law’s defenders in the media and academia don’t want that to happen, so the polls they concoct assume the Burwell challengers are trying to undermine the law and Congress must do something to restore those subsidies.

Remember that the next time you see a poll about Burwell (or any other politically-charged issue) that doesn’t make any sense. Chances are, pollsters are begging the question—and doing it to keep Americans in the dark.