At least 57 times in 2017, and many more last year, Georgetown’s residents paid EDF, a company owned 84.5% by the government of France, around 6 cents per kilowatt hour for electricity produced in the middle of the night when demand was low—so low, in fact, that because of tax incentives and government subsidies, the price for power was negative.

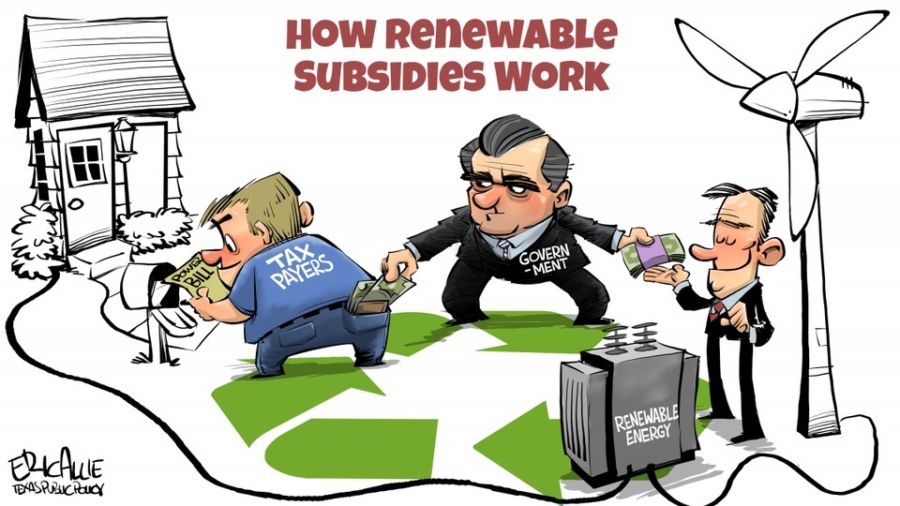

Put simply: Texas taxpayers paid the French government for power and then, to add insult to injury, paid the grid to take the excess power off their hands.

Georgetown (pop. 71,000), 25 miles north of Austin, and its Republican mayor, Dale Ross, became stars of the international green movement when, in a man bites dog sort of way, they were celebrated for going 100% renewable.

A conservative town in red Texas led by a Republican mayor going green – how cool is that?

Reality is catching up with the hype.

In the past few weeks, Georgetown Utility Services, the city’s municipal utility that provides all residents with their electricity, announced a $13 a month rate hike after reluctantly reporting more than $20 million in losses on the electricity market over the past four years. Many residents have reported far higher electric bills as the city digs itself out of a costly fiscal hole.

Then city bureaucrats disputed the notion that the city ever claimed to be 100% renewable, with information revealed by the city last week indicating that 36% of the city electricity last year was generated by natural gas, with the remainder produced by wind and solar.

But, politicians love the limelight, and claiming “We’re 64% renewable!” doesn’t quite have the same virtue signaling allure as 100%.

In the meantime, city residents and the local paper, The Williamson County Sun, have been pressuring the city and its utility to release more information about its electric contracts. The city has resisted calls for transparency, citing competitive concerns (though public Security and Exchange Commission filings hint at some of the contract terms). Yet, while most Texans can pick and choose their electric providers, there is a carve-out in state law granting government-enforced monopoly powers to municipal utilities and co-ops. Competition is irrelevant to Georgetown, as the people and businesses it provides electricity to have no choice in their electric provider.

Returning to EDF (Électricité de France), Georgetown inked a 20-year deal for 144 megawatt-hours of capacity from the Spinning Spur 3 windfarm in West Texas. The challenge with wind power is that in most places in the country, the wind blows most at night, when the electricity isn’t needed as much. Chasing the 100% renewable claim led Georgetown to enter into a flat rate agreement with the French, paying the same for the unreliable power night or day, even if the market price was negative. Thus, on windy nights, when electricity demand is low, Georgetown often produces a surplus of power. Under its contract with EDF, Georgetown must buy the power and, because electricity must be consumed the moment it’s produced, the city has to sell the power onto the Texas grid.

For instance, on two different occasions in 2017, an 8-hour span on the blustery night of November 27-28 and a 10-hour period on the evening of December 3-4, ratepayers paid the grid about $13,000 to take power that they had already paid the French about $120,000 to generate.

About 85% of Texas operates off an electric grid with its own competitive market-pricing system, making it largely free from federal regulation. So, how do wind producers end up making money off of negative prices? It’s complicated.

Between the federal Production Tax Credit (available through the end of this year for wind facilities that started construction by December 31), Investment Tax Credit, Obama-era stimulus funds, and Texas property tax abatements, wind producers make so much money from government subsidies that they make money even if they have to pay others to take their power.

The challenge with ostensibly cheap, but unreliable electricity, is two-fold. First, solar and wind operators who dump no-cost subsidized power into the grid crash the economics for the reliable generators who pay for their fuel, operations and maintenance. Second, as reliable power generators leave the market, the grid becomes increasingly unstable, putting consumers at risk of black outs and brown outs.

There is an equitable way address this problem that doesn’t saddle consumers with risk and higher costs: demand that unreliable (non-dispatchable) renewable generators guarantee dispatchable power as a condition of connecting to the grid. Wind and solar producers would then be forced to guarantee power, something they can’t do alone, by either contracting with traditional power producers, or by building large storage battery arrays capable of capturing the surplus power they generate on cool, sunny days or windy nights. These measures will, of course, make solar and wind power more expensive—but that extra cost will reflect the reality that, in a modern economy, we expect electricity 24/7/365.

In the absence of such measures, grid operators will be forced to subsidize reliable generators, as has been the case to the extreme in Germany and is becoming a more pressing concern in America.