The U.S. Census Bureau issued its annual reports on poverty in America on Sept. 10. Once again, California had the nation’s highest poverty rate, 18.2% over the last three years surveyed, using a measure of poverty that accounts for regional cost differences and a larger array of government welfare and expenses. California’s Supplemental Poverty rate was proportionately 38% higher than the national average, 13.2%.

California’s Supplemental Poverty measure has been improving as the state’s unemployment rate dropped from an annual average of 12.2% in 2010 to 4.8% in 2017. But, during that entire time California has logged the nation’s highest poverty rate. (The Official Poverty Measure tells a different story—but the half-century-old measure assumes the cost of living in Manhattan is the same as it is in Fresno.) The main reason why California’s poverty rate has remained stubbornly high—proportionately 13% higher than Mississippi’s 16.1% and 26% higher than arch-rival Texas’ 14.4%—is that California’s housing costs have remained among the highest in the nation.

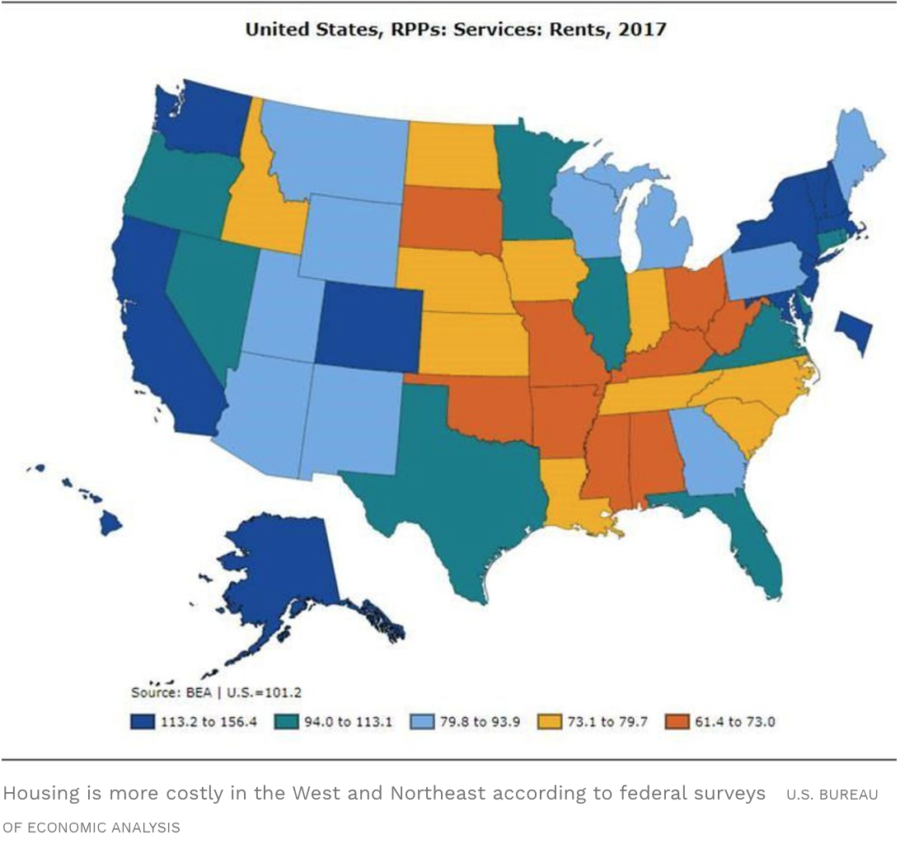

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated that California’s rent index (a broad measure of real estate costs that includes owner-occupied housing) was 153.7 of the U.S. average of 100 in 2009, dipping to a low of 147.3 in 2015 and then rising to 150.6 in 2017 as California’s recovery from the Great Recession caused housing demand to outstrip supply.

California’s new housing stock has been severely restricted by the state’s myriad of web of development fees, restrictive zoning rules, environmental laws—including greenhouse gas restrictions—and lawsuits. Now it’s about to get much worse, with statewide rent control further discouraging new investment in the state.

Just as Census was reporting California’s worst in the nation poverty rate, the California Legislature was sending Gov. Gavin Newsom Assembly Bill 1482, a measure which imposes a 5% above the rate of inflation annual cap on rent increases for rental properties 15 years or older—in other words, most of California’s homes and apartments. The California Association of Realtors said that the bill will, “…impose onerous standards upon small property owners and, in turn, exacerbate the state’s housing crisis.”

In addition to rent control, the bill strengthens already-strong tenant protections, now barring property owners from pursuing evictions without a government-approved reason.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is expected to sign the bill into law.

In Texas, the cost of housing is still below the national average, with the federal government estimating the rent index there at 94.5 compared to the national index of 100 in 2017. In 2009, Texas’ rent index stood at 88.2. It has seen an increase in every year of the past eight. This, in turn, has contributed to Texas’ poverty rate creeping above the national average even as its unemployment rate dropped from 8.1% in 2010 to 4.3% in 2017.

In past years, Texas’ housing market has readily kept up with demand. But, as Texas has grappled with growth and its major urban centers have trended blue, restrictions on development have started to slow the availability of supply and increase the cost of housing.

Still, relative to California, Texas remains a bargain. This is largely the reason California continues to see a strong domestic outmigration of residents, losing a net of 138,000 people in 2017, the largest share of whom moved to Texas, while in-migration to Texas continued, though at a weaker pace than in recent years, netting a total of 57,000 new residents from other states in 2017. California made up for its loss of domestic residents by receiving 316,000 people from other nations, while Texas saw 216,000 people move in from abroad.

One telling statistic about the migration connection between the nation’s two most-populous states comes from U-Haul, where a mover seeking to rent a 20’ truck would pay $3,255 to move from San Francisco to Austin but only $1,003 to head back west—about a 3-to-1 ratio reflecting the cost to U-Haul the deadhead empty trucks back to California so they can be used to relocate more families out of state. But, in 2009 at the height of the recession, the imbalance was greater than 8-to-1.

The evidence from the housing and job markets in California and Texas suggests that California’s policymakers are doing their residents no favors in restricting investment in new housing.

Unfortunately, data from Texas suggests that the Lone Star State is gradually losing its unique advantage and, by 2030, may very well see its cost of living catch up with the national average, driven up by rising housing costs boosted by local government anti-growth policies.