The historic passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act a year ago set off a surge of hiring across America. Since then, private employers added some 2.4 million employees through November 2018, according to the employment reportreleased by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics today.

Further, the federal state jobs report shows that low-tax states have added private sector jobs at a 70.5% quicker pace than in high-tax states in the 11 months since the 2017 federal tax cut legislation became law.

One important aspect of the 2017 tax law was its limitation of the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction for filers who itemize their individual income taxes. The new tax code limits the SALT deduction to $10,000 per household, reducing the federal subsidy of state and local taxes. As a result, the federal tax law change acted to change the relative tax burden at the state level as if all 50 states adjusted their tax rates at once. So while most taxpayers received a federal tax cut, some higher income earners in high-tax states like California saw a smaller tax cut than their counterparts in low-tax states like Texas. A select few, however, saw an increase in their overall tax burden.

Since businesses with fewer than 100 workers employ 57% of the U.S. workforce and a large share of these firms are organized as sole proprietorships (where the small business owner pays personal income taxes instead of corporate income taxes), it stands to reason that the new tax law’s limitation on the SALT deduction may have an effect on job growth at the state level. This is likely because the ability to make and keep more of the money you earn is even more affected by the taxes in your home state.

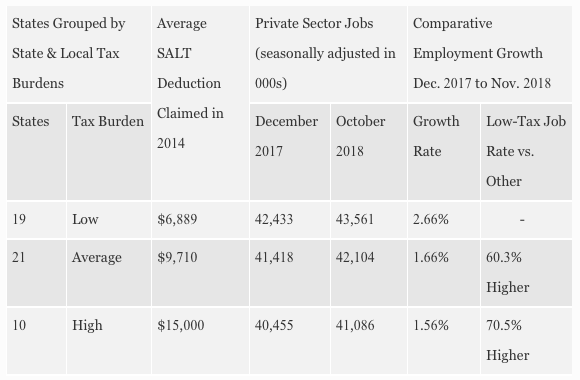

The monthly state level jobs data supports the theory that the tax law has fundamentally altered the tax incentive environment at the state level. This is clear when looking at the 50 states and separating them into three tax levels, each having about the same employment base. Looking at the average itemized SALT deduction in 2014, there are 19 low-tax states, 21 medium-tax states, and 10 high-tax states.

Since the Trump tax cut in December 2017, private sector job growth has been 70.5% higher in the low-tax states than in the high-tax states through November 2018.

Before the tax cut, job growth in the low-tax states was marginally higher than in the high-tax states over the prior two years.

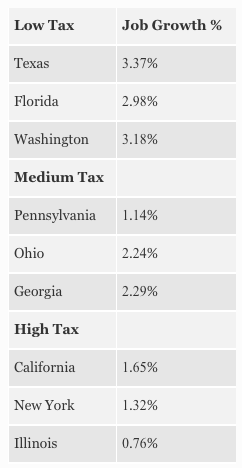

The table below shows private sector job growth from December 2017 to November 2018 in the three most-populous states in each tax category. The three most-populous low-tax states do not have a personal income tax.

Nationwide, the rate of private sector job growth over the past 11 months was 2%. Of the 19 low-tax states, 13 experienced job growth at or above the national average. Among the 21 medium-tax states, seven saw faster job growth than the nation as a whole. With the ten high-tax states, however, only two, Oregon and Maryland, added jobs at a faster rate than did the nation.

In Oregon’s case, that state was at the lowest end of claimed SALT deductions, with an average of only $11,800, compared to $21,000 in New York. Further, relative to California’s very high taxes, Oregon’s tax burden seems a comparative bargain, leading many Californians to make the move north. As for Maryland, it, along with Virginia, a mid-range state for taxes, both continue to benefit from the growth of the federal contractor workforce in the greater Washington, D.C. area.

Along with the incoming House Speaker Rep. Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), many Democrats (especially those representing high-tax states) would like to repeal the $10,000 cap on SALT deductions, even though an analysis by a left-of-center think tank determined that 56.5% of the tax break would accrue to households in the top 1% of income.

Seeking to restore the full SALT deduction isn’t merely seen as a favor to wealthy campaign contributors. Restoring the full deduction would cushion the full measure of blue state taxation on many middle income families, and that has potential political ramifications.

Lastly, a recently released study of interstate business migrations out of California estimates that high taxes, a bad lawsuit climate, and a heavy regulatory burden prompted 1,800 businesses to leave the Golden State in 2016. Joe Vranich, who makes his living as a business relocation consultant, further calculated that in the nine years ending in 2016, some 13,000 companies left California, with the No. 1 relocation destination being Texas. This steady stream of businesses leaving California is one of the drivers of its below-average job growth rate.

Continued high job growth in low-tax states and sluggish job growth in the high-tax states should prompt legislators across the nation, who are convening for their 2019 legislative sessions, to take a hard look at trimming state spending and taxes to boost their economies.