Vocational programs have long been required to help their students secure gainful employment, but until the early 2010s, gainful employment had never been defined. The Biden administration has just released a draft of the latest Gainful Employment regulations, and, like the previous iterations, it would terminate financial aid eligibility (Pell grants, students loans, etc.) for postsecondary programs that fall below certain thresholds designed to measure gainful employment.

Historical Background

The proposed regulations mark the third round of attempts to define gainful employment.

The first round was in 2011, when the Obama administration first tried to define it. The courts ultimately threw the regulations out because the administration had set repayment-rate thresholds to ensure that a predetermined and arbitrarily chosen number of for-profit programs would fail, and because it would have given the Secretary of Education veto power over new programs at for-profit colleges (an unprecedented intrusion into colleges’ educational offerings).

The second round of gainful employment came in 2014, when the Obama administration released new regulations. These used two student loan debt-to-earnings metrics, and they survived court challenges. It took several years for the regulations to take effect and for the Department of Education to collect the necessary data to conduct its gainful employment tests. By the time it started releasing data in early 2017, the Trump administration quickly stopped enforcing the regulations and ultimately rescinded them.

The third round is the Biden administration’s recently proposed regulations. This iteration uses almost the same debt-to-earnings metrics as the 2014 regulations (though it drops a probationary rating). It also introduces a new test utilizing an earnings floor—programs whose graduates earn less than the typical high school graduate would fail the test. Thus, postsecondary programs will lose eligibility for federal financial aid programs if their students’ debt is too high relative to earnings (as determined by the debt-to-earnings test) or if their students earn too little (as determined by the earnings threshold test).

What should we make of Biden’s Gainful Employment? Like most policies, these regulations are a mix of good and bad ideas.

The Good

The first two rounds of gainful employment have led to a number of promising developments, and the Biden administration builds and expands on these. In particular, gainful employment was the first federal program to make two important advances in accountability.

First, focusing on programs (e.g., the bachelor’s degree in accounting at Purdue) rather than entire institutions (e.g., Purdue) allows for more targeted enforcement and avoids punishing good programs at bad schools or letting bad programs at good schools escape accountability.

The second advance was incorporating labor market outcomes into accountability metrics. Labor market outcomes had been ignored prior to gainful employment—this was a huge oversight, given that around 90% of students attend college to improve their job prospects. The regulations considered labor market outcomes in a sensible way, defining the required earnings relative to student loan debt.

The Biden regulations bring a third advance in accountability: they set a minimum floor for earnings. When set reasonably (see below), this can serve as a very useful metric to eliminate subsidies for programs that do not benefit students.

The Bad

However, the Biden regulations also have some flaws.

First, while the concept of an earnings floor makes sense, the Biden administration plans to set one floor for all programs—any program where graduates earn less than the typical high school graduate would lose eligibility. High school graduate income makes sense as a threshold for undergraduate certificate programs or associate degree programs, since the high school wage is a good counterfactual estimate of graduates’ salaries if they didn’t attend these programs. But the counterfactual salary for a doctoral program shouldn’t be the high school wage; it should be the typical salary for a bachelor’s degree recipient, since that is the wage most doctoral students would receive if they didn’t attend their program. Using one wage for all credential levels is a mistake.

Second, compared to the 2014 iteration, the Biden regulations eliminate a probationary rating on the earnings tests. But it would be better to have rewards and sanctions that scale up and down as performance changes, rather than an all-or-nothing approach.

Third, the Biden administration also introduced a variable amortization schedule, where debt payments for doctoral degrees are amortized over 20 years, while those for associate degrees are amortized over 10 years. Since a college education does, in theory, pay off over a lifetime, longer amortization schedules can make sense—but these differences are too arbitrary and too large to be defensible. If the administration insists on a variable schedule, it would be better to use actual student-repayment rates by credential to determine these values.

Fourth, and most importantly, like the previous iterations of gainful employment, the Biden version is selectively targeted. All vocational programs are subject to the regulations, but vocational programs are defined to include all for-profit programs and any certificate programs at public or private non-profit colleges. This leads to nonsensical results:

As a matter of logic, this categorization failed miserably. A bachelor’s in nursing program at a for-profit college was subject to the Gainful Employment regulations, while a bachelor’s in nursing program at a public college was not. Similarly, a master’s in social work program at a for-profit college was considered vocational, but a master’s in business administration (MBA) program at a public college was not. An MBA program is perhaps the clearest possible example of a vocational program, yet as long as the MBA program was housed at a public or private nonprofit college, it would not be considered vocational and would therefore not be subject to Gainful Employment.

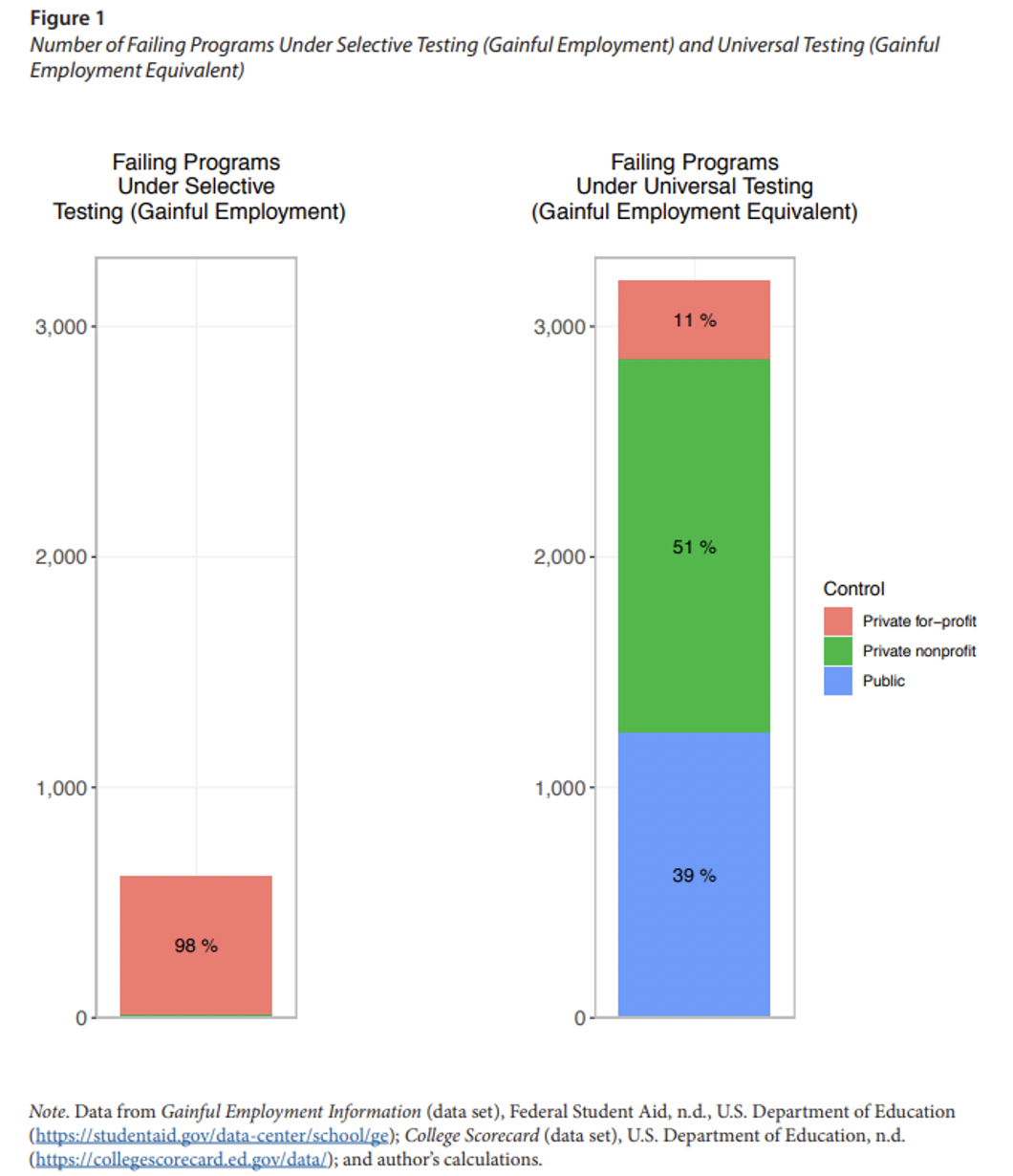

This selective targeting also misses huge numbers of failing programs. The 2014 Obama regulations, for example, neglected the vast majority of failing programs, as shown in the figure below (from this paper).

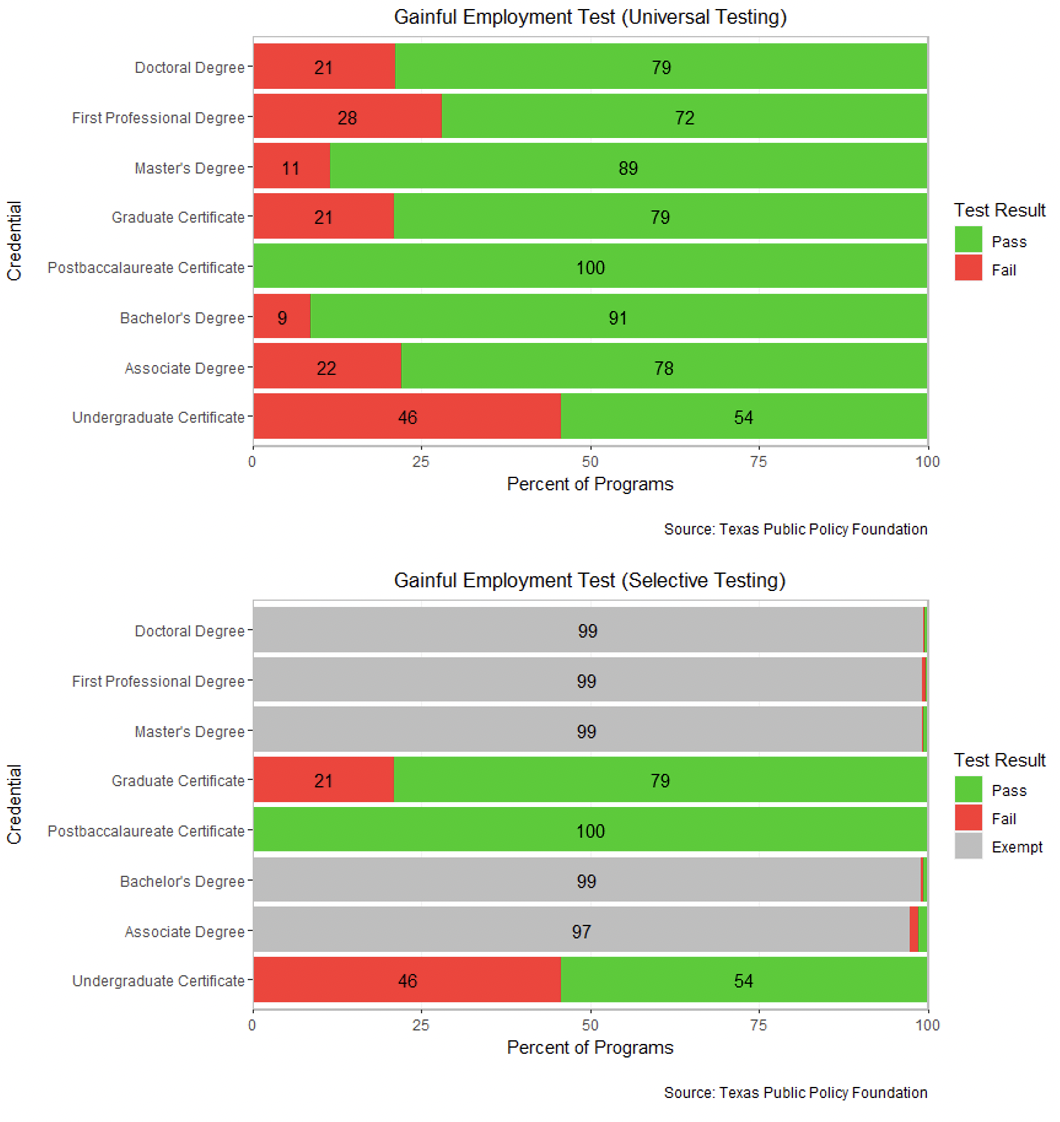

Rather than learning from the flawed Obama administration approach, the Biden gainful employment regulations simply repeat this mistake. In the figure below, the top panel shows the gainful employment test results when the regulations are applied equally to all colleges (universal testing). The bottom panel shows the results under the Biden administration’s selective testing, in which 99% of doctoral, professional, master’s, and bachelor’s degrees are exempt from accountability, as are 97% of associate degree programs. Yet, if the tests were applied to all programs, 21% of doctoral programs would fail, as would 28% of professional programs, 11% of master’s programs, 9% of bachelor’s programs, and 22% of associate degree programs.

The regulations will cull undergraduate certificate programs the most, where 46% of programs will fail.

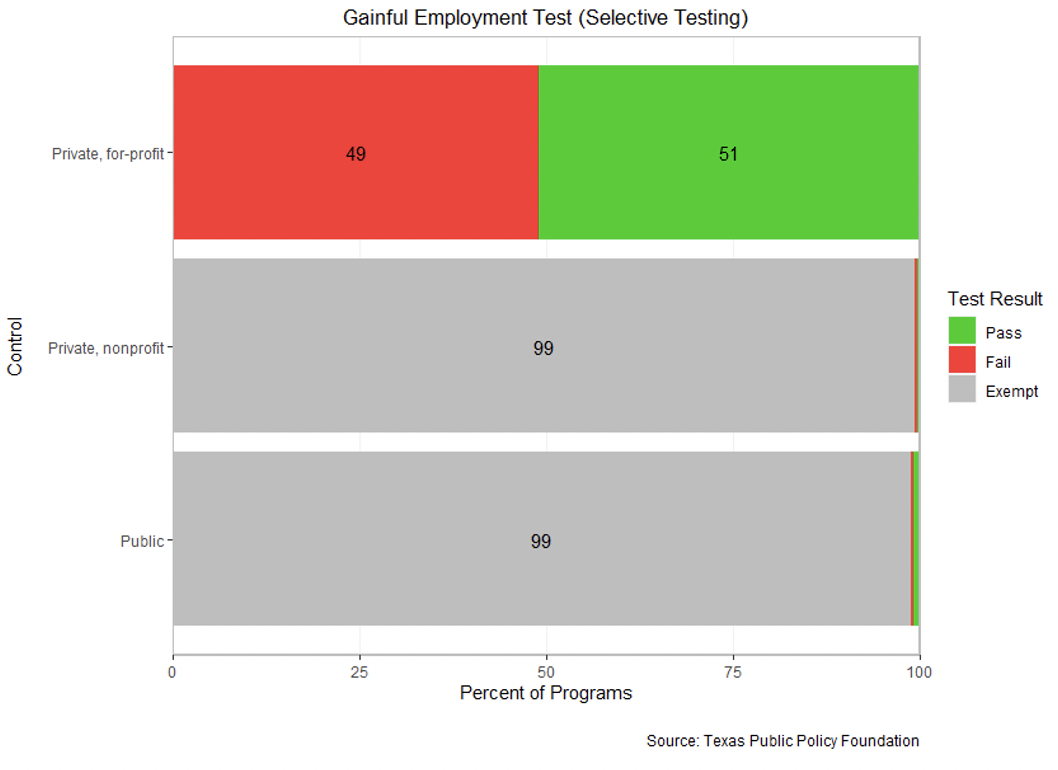

But the Biden administration’s real targets are the for-profits, just as they were for the Obama administration. As the figure below shows, Biden will shut down almost half of the programs at for-profit colleges, while exempting 99% of programs at public and private nonprofit colleges.

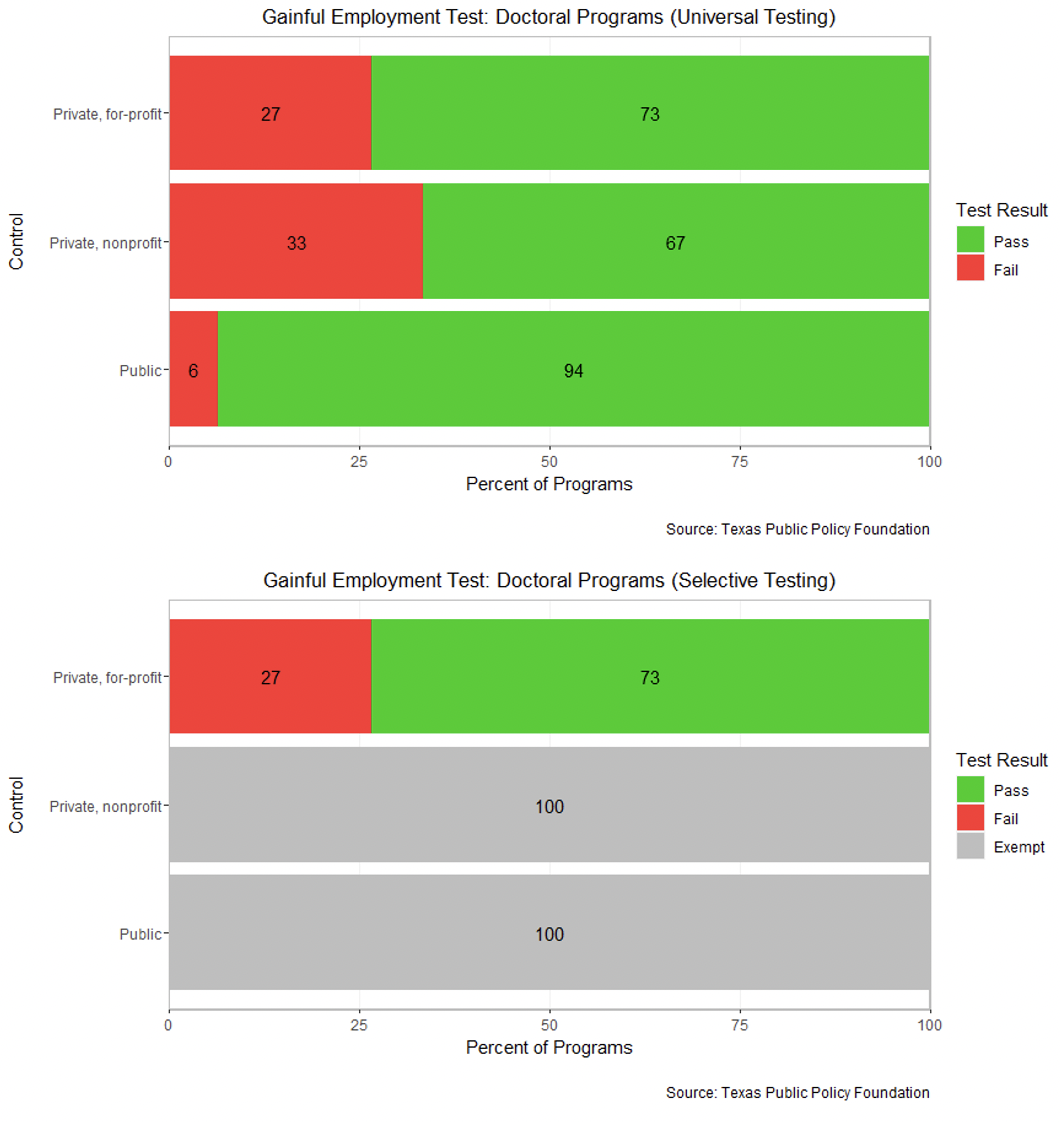

The for-profits do underperform (49% of programs fail, compared to 15% at private nonprofits and 8% at publics under universal testing), but this is due partly to the disproportionate number of undergraduate certificate programs they offer (which the regulations decimate). There are some credentials where the for-profits do not underperform, yet these institutions are still singled out by the regulations. Consider doctoral degrees. If gainful employment were applied to all doctoral degree programs, 27% of for-profit programs would fail, while 33% of private nonprofit programs would. Yet the Biden administration exempts all of the private nonprofit programs from the regulations while applying them to the for-profit programs.

Conclusion

Overall, the three rounds of gainful employment have introduced a number of worthwhile approaches to accountability (e.g., program rather than institutional evaluation, defining excessive debt relative to earnings, and establishing earnings floors) that should be utilized in future accountability systems. But selective targeting is a deal-breaker. None of us would think that a criminal justice system that only punished left-handed people was legitimate. A college accountability system that targets everything at for-profits while exempting 99% of public and nonprofit institutions is likewise incomplete. The Biden administration should not move forward with such a flawed approach. If it does, Congress should repeal the regulations using the Congressional Review Act. And if Congress doesn’t, the next Republican presidential administration should rescind the regulations and replace them with an accountability system that applies to all colleges.