There is an ongoing dust up involving the First Amendment, allegations of prohibited viewpoint discrimination and legislative immunity in the Texas Senate. It’s fascinating stuff for political scientists, political practitioners, and journalists.

It started on Thursday, February 27, when a man testified at a Texas State Senate hearing wearing a t-shirt that said, “F**K the POLICE,” (but his shirt featured all the letters) and, to drive the sentiment home, accompanied by an image of a hand with the middle finger outstretched.

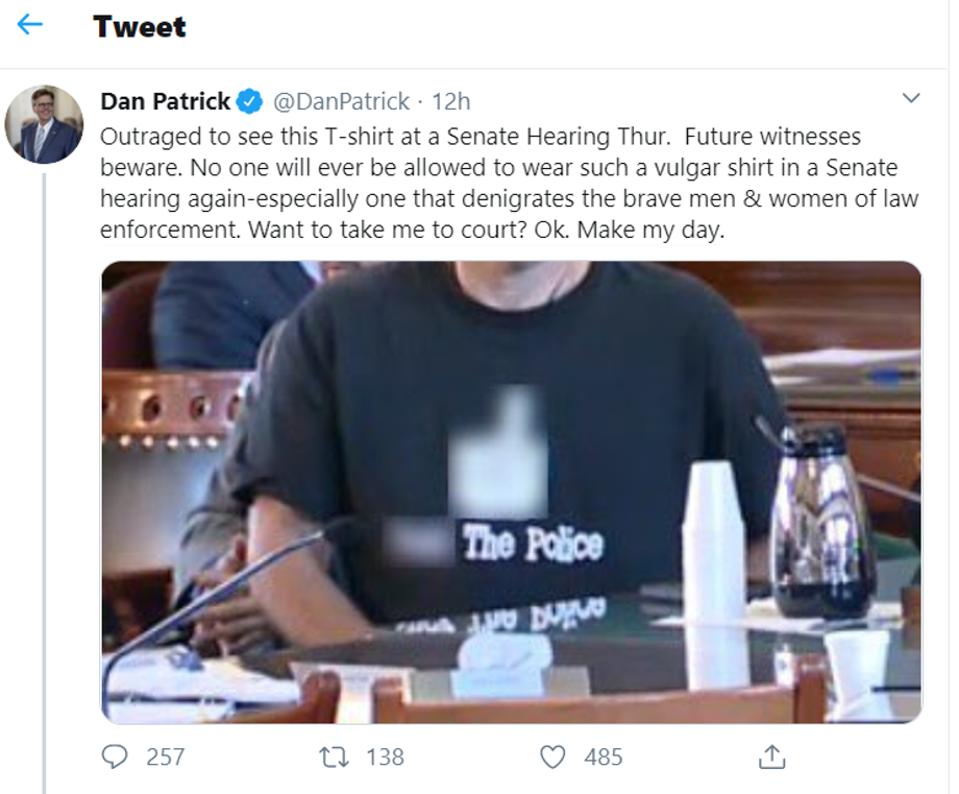

After learning about the hearing, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick tweeted out:

Outraged to see this T-shirt at a Senate Hearing Thur. Future witnesses beware. No one will ever be allowed to wear such a vulgar shirt in a Senate hearing again-especially one that denigrates the brave men & women of law enforcement. Want to take me to court? Ok. Make my day.

Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick tweeted out his disapproval of people wearing vulgar shirts … [+]

His tweet was met with a volley of criticism by First Amendment advocates who maintained that Lieutenant Governor Patrick—and the Legislature in general—doesn’t have the right to abridge speech or pick and choose between types of speech. (Note to readers outside of Texas: the lieutenant governor in Texas is the most powerful lieutenant governor in the nation in that the person in that office actually runs the State Senate, not unlike how the Speaker of the House runs the House.)

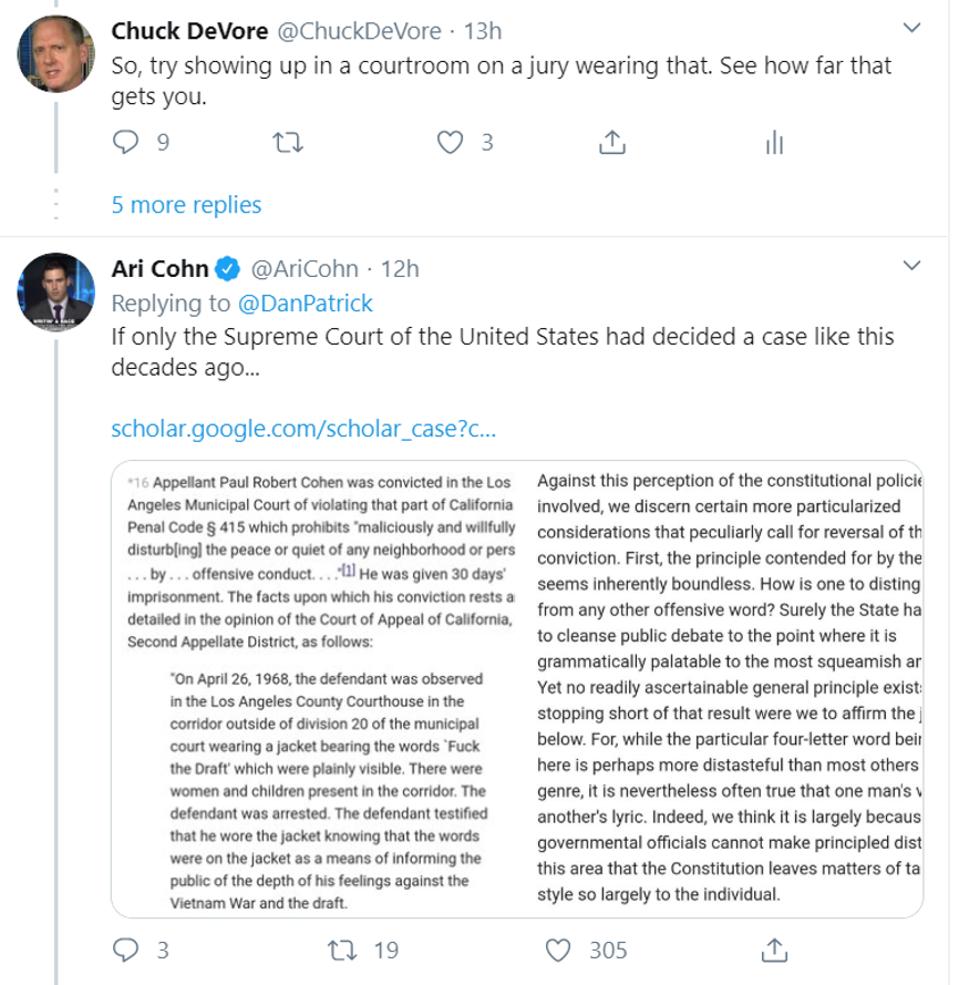

Common in the citations to make their point was a U.S. Supreme Court decision from the Vietnam era. In Cohen v. California, the court ruled on the case of a 19-year-old man who was arrested for wearing a jacket that read, “F**k the Draft, Stop the War,” into a California courthouse. The court overturned his arrest and conviction on a 5-4 decision that determined that California’s law that prohibited the display of offensive messages was a violation of the freedom of expression as protected by the First Amendment.

Cohen v. California, decided in 1971, was often cited as the case that would prevent viewpoint … [+]

It is interesting to note that in the Cohen case, the appellant did wear his offensive jacket in the courthouse hallways but removed it upon entering a judge’s courtroom, folding it over his arm. He was only arrested after leaving the courtroom for having worn the jacket in the public hallways of the courthouse. Had the reverse been true, and the judge ordered him ejected from his courtroom for wearing the jacket, and he resisted, the ruling likely would have gone the other way.

Of course, judges to this day enforce rules of decorum in their courtrooms—look at any jury summons—it will instruct the prospective juror on the acceptable attire and conduct in a courtroom.

First Amendment advocates will admit to this but are quick to add that judges should not engage in viewpoint discrimination—though many still do today.

Which brings up back to Lieutenant Governor Patrick’s tweet. Let’s break it down to its chief components.

First, that the shirt in question was vulgar and has no place in a Senate hearing.

Second, that the shirt was especially offensive in that it denigrated “the brave men & women of law enforcement.”

Third, that if you don’t like it, you can take the lieutenant governor to court.

To the first question, while most analysts would admit that, just as a judge can set rules for their courtroom, so to can a legislative body set rules for decorum in the deliberative portions of their chambers, such as the floor and in hearing rooms. These are seen as different than public places, for example, the rotunda in a state capitol building or a public sidewalk.

Even so, Ari Cohn formerly a director at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), a group that brings many successful free speech lawsuits against educational institutions, insisted that there is no decent enforceable legal definition of vulgar. So, even if the Texas Senate were to uniformly enforce a ban on “offensive” clothing, it wouldn’t stand, presumably if any clothing with a message were allowed, even something as innocuous as a shirt that read “Lake Travis High School.”

We’ll return to this question in a moment.

The second issue is that the vulgar shirt in question was particularly offensive as it denigrated law enforcement officers. This is where the accusation of viewpoint discrimination focused. The lieutenant governor cannot, his critics claimed, pick and choose between messages he likes and those he doesn’t like—either take them all or ban them all.

And, lastly, if you don’t like Lieutenant Governor Patrick’s actions, you can take him to court.

But—and here’s the big question—is the Legislature in the course of its official business, subject to any restraint by the courts?

I would argue that, in its internal operations, the answer is an emphatic “No!”—unless specifically proscribed by the Constitution or a state constitution.

First of all, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Minnesota State Bd. for Community Colleges v. Knight in 1984 that there is no constitutional right to force officers of the State acting in an official policymaking capacity to listen to the views of the public. Secondly, in Curnin v. Town of Egremont, decided by the First Circuit Court of Appeals with the U.S. Supreme Court allowing the ruling to stand in 2008 (denying certiorari), that “The First Amendment does not give non-legislators the right to speak at meetings of deliberating legislative bodies…” and that

“The Supreme Court has never extended First Amendment forum analysis to a deliberating legislative body or to the body’s rules about who may speak. While no Supreme Court case is directly on point, the Court has addressed the underlying issue of the public’s ability to address government policymakers:

The Constitution does not grant to members of the public generally a right to be heard by public bodies making decisions of policy․ Policymaking organs in our system of government have never operated under a constitutional constraint requiring them to afford every interested member of the public an opportunity to present testimony before any policy is adopted․ Public officials at all levels of government daily make policy decisions based only on the advice they decide they need and choose to hear. To recognize a constitutional right to participate directly in government policymaking would work a revolution in existing government practices.”

The court goes on to note that, “Under the Speech or Debate Clause of the U.S. Constitution, Article I, section 6, there are constitutional separation of powers protections for Congress.” Further, that “The purpose of the Clause is to insure that the legislative function the Constitution allocates to Congress may be performed independently.” That “This immunity extends to injunctive relief.” And finally, that, while, “No explicit federal constitutional protections cover state or local legislative bodies. …there are still federalism and separation of powers concerns, which have led to the adoption of similar immunities for state legislators,” citing the Knight decision.

Turning to the Texas Constitution, we see in Article III, governing the Legislative Department, Section 15, that “disrespectful or disorderly conduct” by “any person not a member” in the presence of the a house conducting its business can result in imprisonment for up to 48 hours. Given that this action would not involve executive branch law enforcement or judicial branch court proceedings, it’s likely that such an imprisonment would not accrue to someone’s arrest record or criminal record as the violation would be unique to the Legislature.

Lastly, going to the heart of the matter of “viewpoint discrimination,” is it permissible, under the any rules of a legislative body, that a committee chairman might only accept testimony from all Democrats or all Republicans? Yes, of course. As the federal courts have noted, “Public officials… daily make policy decisions based only on the advice they decide they need and choose to hear.”

I’d argue that a hearing where ten Republicans testify with no Democrat witnesses is a far more egregious form of viewpoint discrimination than is banning an offensive shirt, yet, it’s perfectly acceptable, legal, and constitutional for a legislative body to decide to do so and there’s nothing the courts can do about it. It’s done in the U.S. Congress all the time. It’s an internal matter of that legislative body. The legislative function must be performed independently. Anything less would admit to judicial supremacy. Don’t like it? Win the majority and run the house as you will.

Of course, if the courts did try to meddle in the internal affairs of the Legislative branch, that branch has the tools to fight back: they can impeach and remove judges, if they muster the political will to do so. They can also use their budgetary powers in creative ways so as to concentrate the minds of an overambitious co-equal branch.

While such actions are constitutional, whether they should be done or not crosses into ethical behavior and considerations of political prudence. Just because a legislative majority can do something, doesn’t mean that they should or that there might not be consequences come election time.

Bottom line: Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and other officers of the Texas Legislature are free to order the official and internal affairs of their respective legislative chambers as they wish, in accordance with the will of that body and free from interference of either the judicial or executive branches.