Choosing whether and where to attend college is the most important financial decision of a young person’s life. Yet, in general, we withhold the information that would allow students to make informed decisions. The most blatant example is hiding the cost of college.

In 2018, Stephen Burd, Rachel Fishman, Laura Keane, Julie Habbert, Ben Barrett, Kim Dancy, Sophie Nguyen, and Brendan Williams at New America published Decoding the Cost of College, which documented how confusing financial aid offer letters were at the time. One of the most shocking findings was the extremely confusing (often deliberately so) way loans were described. For unsubsidized student loans, the authors “found 136 unique terms for that loan, including 24 that did not include the word ‘loan.’” The New America team conclusively documented that many college students are being forced to make the biggest financial decision of their young lives while being deliberately blindfolded.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t appear to have been much progress since then. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) recently conducted its own investigation of financial aid offer letters. The results are as dismal as the New America analysis. GAO examined how many colleges follow each of several best practices. The results are shocking. Each of the following should be considered a scandal on its own. Together, they reveal a higher education financing system that is allowing colleges to mislead students on a massive scale.

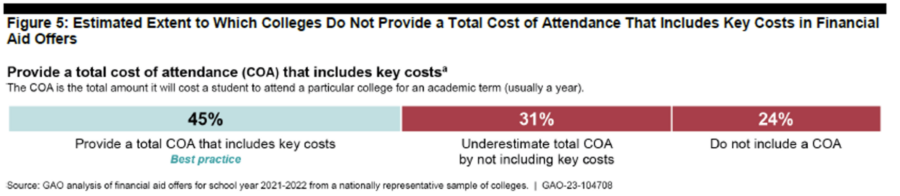

1. Less than half of colleges tell students the total cost of attendance

The cost of attendance (COA) is the total cost of attending a college, including monies that go to the college, like tuition and fees and room and board, but also estimated expenses for things like books and travel. COA is the most accurate total cost a college can provide a student and is foundational to determining how much federal financial aid a student can get. Yet, as the figure below shows, only 45% of colleges provide an accurate COA to students.

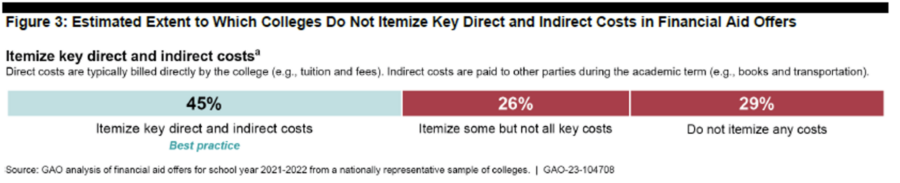

2. Less than half of colleges itemize costs

In addition to providing the total COA, colleges should itemize costs. Only 45% of schools do so.

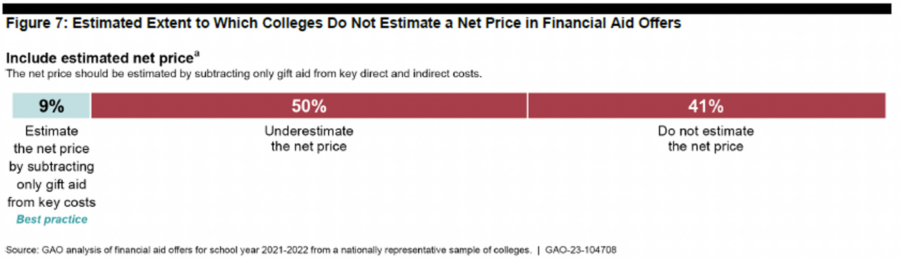

3. 91% of colleges obscure or mislead students about the net price

Given financial aid like Pell grants and scholarships, there can be a big difference between the starting cost of a college (called the sticker price) and the actual cost of a college, called the net price, which is found by subtracting grants and scholarships (called gift aid) from the sticker price. Yet 41% of colleges don’t report the net price at all, and 50% underestimate the net price by subtracting things like student loans, which need to be repaid (loans are a method of paying the net price—they don’t reduce the net price). Only 9% of colleges provide students with the true net price they need to pay.

4. Almost half of colleges do not follow any best practice regarding the costs of college

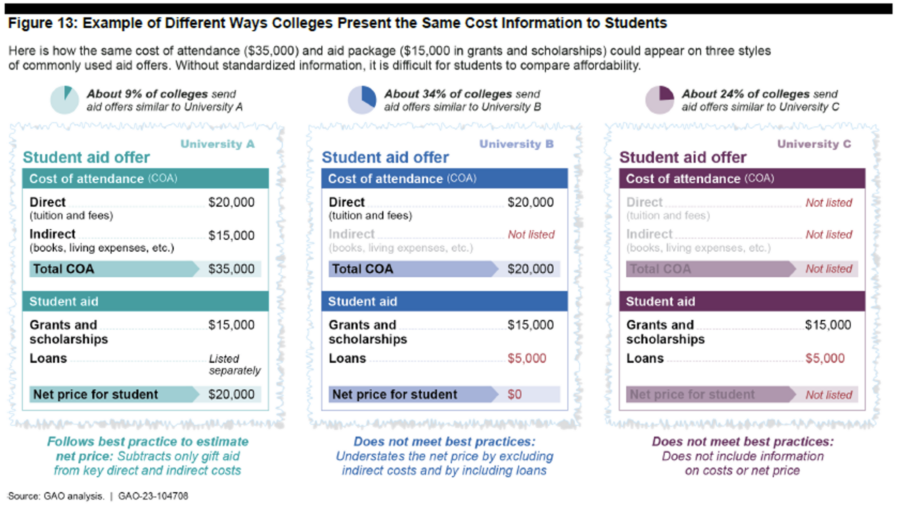

The three practices discussed above—providing the total costs, providing an itemized list of costs, and providing the net price—are basic, fundamental requirements for allowing students to make informed decisions. Yet fewer than 10% of colleges provide all three, and 48% of colleges “do not follow any of the three best practices for informing students about how much they will need to pay for college.”

Consider the GAO figure below. The best practice is shown in the far-left panel, wherein students are given an itemized list of costs, the total cost, and the net price after accounting for grants and scholarships. Only 9% of colleges provide students with this information. As the far-right panel shows, 24% of colleges don’t provide the student with any information on costs, listing only the financial aid available. As shown in the middle panel, 34% of colleges mislead students by omitting indirect costs like books and subtracting loans when calculating the net price.

What should be done?

There are two main ways to fix this problem.

The first remedy would be to mandate standardized disclosures. As the GAO report notes,

Federal law generally requires standardized consumer disclosures for certain other complex financial products, such as mortgages, private education loans, and credit cards. Mandated consumer disclosures, like the ones for mortgages, give consumers more information about the costs and terms before they take on a new obligation and can help them shop for the best terms because key information is disclosed in the same way… the lack of similar requirements for clear and standard information in colleges’ financial aid offers makes it difficult for students and parents to compare affordability and make informed financial decisions about how much they will need to borrow.

Standardized disclosures work wonderfully for mortgages, allowing consumers to easily compare mortgage offers. The Department of Education has even published an excellent College Financing Plan, a template that follows all the best practices.

[More from Andrew Gillen: “One Way to Fix Students Loans: Mandatory LRAPs”]

A second remedy would rely on the courts. The law could be loosened to allow and encourage students to sue colleges for fraud or misrepresentation when they provide substantially misleading cost and aid information. Safe harbors could be created for colleges that use the College Financing Plan or closely mimic it. The main advantage of this method is that it imposes less of a one-size-fits-all solution. For example, the College Financing Plan is limited to a single year, but a college’s main selling point may be that students graduate in three years instead of four. The shorter program may save the student a lot of money overall, but it won’t be evident when costs are listed one year at a time. The main disadvantage is that this remedy would take much longer to work, and even if it does, offers to students would be less comparable.

Perhaps both remedies could be combined. Colleges would be required to use the College Financing Plan. However, they could self-certify that they need to make alterations, but any alterations are fair game for student lawsuits on fraud/misrepresentation grounds. In any case, students must have accurate, complete COA information before making the most important financial decision of their lives. The consequences of their financial blindfolding have been disastrous.