Continuing a series of California and Texas comparisons, this piece examines the two most-populous states’ housing policies.

California and Texas have a lot in common; they’re both big and diverse. It’s politics (and the public policy that results) that most separate these two states.

But in one area, housing, Texas is increasingly in danger of replicating California’s errors.

The U.S. Department of Labor announced today that 250,000 new jobs were created in October, far surpassing expectations, as the Trump Administration’s tax cuts and regulatory reforms have sparked an economic boom. Wage gains for working Americans are finally rising as well, passing 3% for the first time since the recession a decade ago.

But what if all those new jobs and impressive wage gains were eaten up by higher housing costs? And what if much of the blame for those higher housing costs was due to local government?

Here’s just one example: As Central Texas has dried out from weeks of heavy rains, work crews are returning to home construction sites to work off a big backlog. But 99 construction sites were greeted by dozens of “red tags” from the City of Austin’s building inspectors that slowed their progress and sent many of them home with some 2,000 inspections to go (inspectors said rains had resulted in mud in streets).

Typically, city inspectors can coordinate with contractors to attempt to address concerns in such a way as to not disrupt construction and deny workers a day’s pay and slow the pace of building.

In this case, the city of Austin chose not to. Attitude plays a big role in how city employees interface with builders.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit Midland, Texas, in the heart of the Permian Basin oil and gas region. I visited with the local homebuilder’s association and was pleasantly surprised to see four city employees participating in the lunch meeting. The manager of the city’s construction inspection team spoke about how construction permits were running 14% ahead of where they were in 2014, the prior peak year for construction in Midland. He was clearly proud of his community and his team.

I spoke with the city employees afterward and asked about their relationship the construction industry. They saw themselves as being in partnership with the community—providing a service to both builder and homeowner. The entire team of city employees were keenly aware that their job was to serve the public, not the other way around.

A five-and-a-half hour drive to the east sits the Texas capital, Austin. Featuring some of the highest local taxes in the state, Austin is fast becoming known for its progressive, activist city council and policies such as mandatory paid sick leave, tree ordinances, and plastic bag bans. The city council’s hostile attitude towards private enterprise—including the construction industry—has gotten worse in recent years.

So, it comes as faint surprise that Austin homeowners and homebuilders are complaining about growing backlogs for electrical inspections—backlogs that cost both time and money. In May, the city’s inspection backlog was approaching 500 and growing. What was supposed to be a wait of five days had mushroomed to weeks or months with added costs to homeowners of $15,000 or more.

A recent survey of the top-20 U.S. urban areas with housing costs out of reach of the average wage earner showed six metros in California with only one—Austin—in Texas.

In much of California, however, homebuilders would be envious at their counterparts in Austin—at least they can build.

In Orange County, California, just down the coast from Los Angeles, only 20% of residents could afford a median-priced existing, single family house, this, in spite of the county’s higher than average wage levels. Across California, 27% of the state’s households could afford a median-priced home of $588,530 in the 3rd quarter of 2018.

Some 61.5% of Texans own their own homes compared to 53.8% in California, the third-lowest rate among the states after New York and Hawaii.

Some of the challenge with out-of-reach home prices and high rent in California is due to what many of the politicians there call a “weather tax” – the premium many California residents are willing to pay for the Golden State’s famously mild climate.

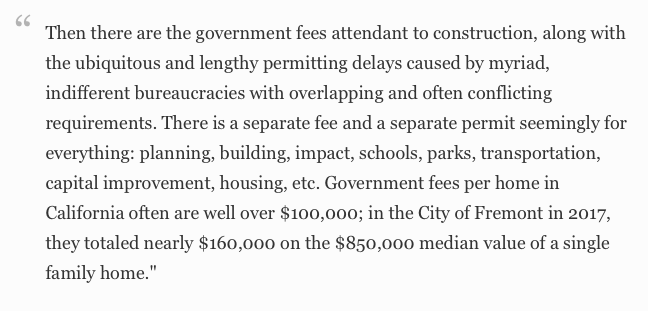

However, blaming the state’s housing costs on the “weather tax” obscures the role that deliberate policy decisions have in causing high costs for shelter. According to the California Policy Center’s Edward Ring:

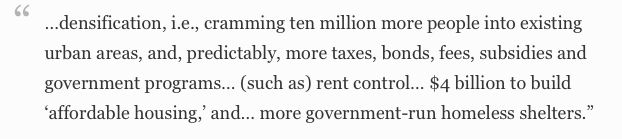

Ring goes on to list California policies that cause artificial housing scarcity, such as preventing growth into suburban areas surrounding the state’s major urban centers. Instead, the politicians who run the state, in league with “environmentalist litigators, public sector unions, and left-wing oligarchs” promote:

In the meantime, elite academics at UCLA with the ear of both politicians and press sniff about the “dogma of private housing.”

Socialist French economist Thomas Piketty theorized in his “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” that wealth inequality has gotten worse and will only grow because capital’s share of income will grow faster than the economy.

But Matthew Rognlie, an economics professor at Northwestern University, disputed Piketty’s thesis while doing his own Ph.D. work at M.I.T. Rognlie found that Piketty failed to see that “Recent trends in both capital wealth and income are driven almost entirely by housing…”

Studying housing cost trends in New York City and California, Rognlie noted that in “markets with high housing costs” those “costs are driven in large part by artificial scarcity through land use regulation.”

Government-caused artificial scarcity is the main reason why, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, California has the nation’s highest Supplemental Poverty rate, at 19%, proportionately 29% higher than in Texas. That the average rent in Houston is $996 vs. $2,420 in Los Angeles shows illustrates a big challenge for the working poor.

Sadly, Austin, and many other major Texas urban areas, are doing all they can to catch up to California. If they are allowed to do so, it will end Texas’ main competitive advantage in attracting hundreds of thousands of Americans fleeing high-tax states such as California, Illinois and New York for the opportunity to live the American Dream in Texas.