Does history suggest that property taxes are too high in the city of Houston? And, if so, have local decision-makers actively helped or hurt the situation?

To help answer these questions, let’s review the city’s 2024 Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR) and gather four types of data—i.e., tax levies, local population, total tax rates, and taxable values—over a 10-year time horizon. Using these audited estimates, we can gauge the growth of government (i.e., tax levy trends), assess its reasonability (i.e., has government grown in response to surging population?), and evaluate whether local elected officials are using their prescribed authority in the tax rate-setting process to properly balance rates and values.

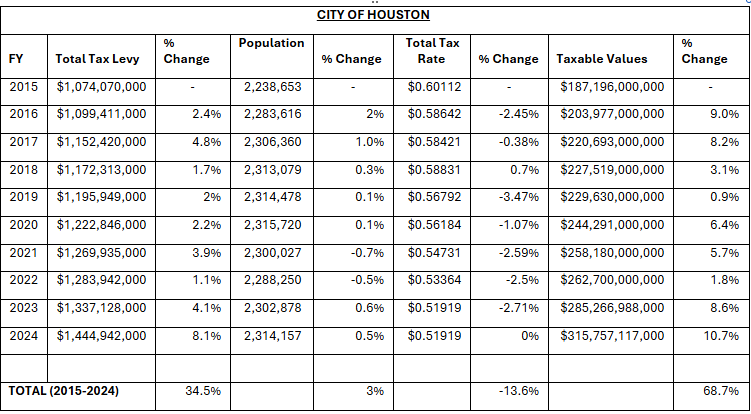

To begin, we can observe that the city’s total tax levy—which may be understood as: “The sum of the maintenance and operation and debt service levies generated by applying a [governmental entity’s] adopted tax rates to its locally assessed valuation of property for the current tax year”—experienced modest growth over the last decade. In fact, from 2015 to 2024, the city’s total tax levy rose from $1.07 billion to $1.44 billion, equating to a 34.5% increase.

Now, on its own, this percentage change does not provide enough context to discern whether it was a reasonable or unreasonable rate of growth. For that, we must compare the decade-long growth in tax levies (+34.5%) with another value of similar significance, like population. By comparing these two metrics, it is possible to gain greater insight into the situation’s fairness.

So here’s what the data shows: In 2015, the number of city residents totaled 2,238,653. By 2025, that figure grew slightly to 2,314,157, resulting in a 3% population change for the time period.

Thus, on the one hand, the city’s main revenue source grew by 34.5% over the last 10 years. On the other hand, its population increased by just 3%.

This dynamic raises a few interesting questions, but chief among them is this—what, if anything, have Houston’s elected officials done to contain or contribute to this disparity?

To explore this question, let’s consider how the city’s total tax rate and taxable values have changed. For clarification purposes, total tax rates refers to the sum of: “a rate for debt service payments—often called the ‘I&S rate’ or interest and sinking fund rate—and a rate for day-to-day maintenance and operations—the ‘M&O rate.’” The term taxable values can be understood as: “[t]he property value you pay taxes on.” In this case, taxable value can be construed to apply on a community-wide basis, rather than on an individual level.

From 2015 to 2024, the city reduced its total tax rate by 13.6%. Simultaneously, total taxable values grew by 68.7%. Hence, rates declined modestly at the same time that property values surged.

While it is true that city officials do not have control over property values (mostly), it is also true that “[l]ocal governments set tax rates.” This means that city officials have the discretion to adopt higher or lower tax rates to adjust for property value growth or decline. The tax rate decision reached by local elected officials every year has a direct and obvious impact on your property tax bill.

Ideally, an “inverse relationship” exists between rates and values, meaning that as one goes up, the other should come down in relatively similar proportion. In this case, the data shows that Houston’s total tax rate declined somewhat over the prior decade but those reductions were overshadowed by a much greater growth in taxable values. As a result, the city’s tax levy increased substantially more than population growth, which offers some partial insight into Houston’s property tax woes.

Moving forward, city leaders would be wise to consider a different approach to property taxes. Namely, officials ought to limit levy growth to population growth, adopt the no-new-revenue (NNR) tax rate or a rate below the NNR, and consider other good government reforms to ease the burden of government on everyday Texans.

Changes like these are needed, both to help families cope with today’s cost-of-living crisis as well as to better discipline the growth of government, which the data shows is warranted.