This commentary originally appeared in The Federalist on July 27, 2015.

Thomas Piketty sent a thrill up the collectivist legs of liberal America with his “Capital in the Twenty-First Century.” In his book, the French economist and academic contends that the rich will get richer because capital’s share of income has been growing faster than the economy, making the return on capital investments increasingly more valuable than labor.

As compelling as Piketty’s thesis is for the Left, he’s wrong. Matthew Rognlie, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology doctoral student in economics, dismantles Piketty in his paper, “A note on Piketty and diminishing returns to capital.” Rognlie’s contention: “Recent trends in both capital wealth and income are driven almost entirely by housing…” Ronglie deploys sarcasm with effect, suggesting Piketty’s book would have been more accurately named, “Housing in the Twenty-First Century.”

Rognlie then makes an interesting insight; housing prices are going up because of artificial scarcity caused by land-use regulation. Put another way, the concentration of wealth is not an issue of the “1 percent” winning while the rest of us lose—it’s an issue of homeowners benefitting from government restrictions on property rights that prevent a free market in homebuilding, restricting supply and driving up prices.

If Rognlie is correct (and the data suggests he is), then the liberal prescription to address growing wealth inequality misses the mark. Further, it complicates the Left’s attempt to capitalize on Occupy populist outrage. Going after homeowners is a much different electoral and rhetorical proposition (especially if you’re still living in your parent’s basement) than going after the vilified “1 percent.”

Government Is the Problem, Not the Market

As for affordable housing, liberals see high housing costs as a phenomenon caused by capitalism. Rather than address government-induced artificial scarcity in housing head-on, the Left proposes additional government intervention to fix the problems callous markets have caused—to address “disparate impact.”

Government-forced low-income housing quotas, tax credits, subprime loans, housing vouchers, high-density urban villages, transit-oriented development (served by government-run buses and trains operated by government-union employees), housing projects built with government bonds, and lotteries for below-market rate homes are proffered as solutions. None of these “solutions” can even remotely come close to generating enough supply to overcome government’s housing-market distortions.

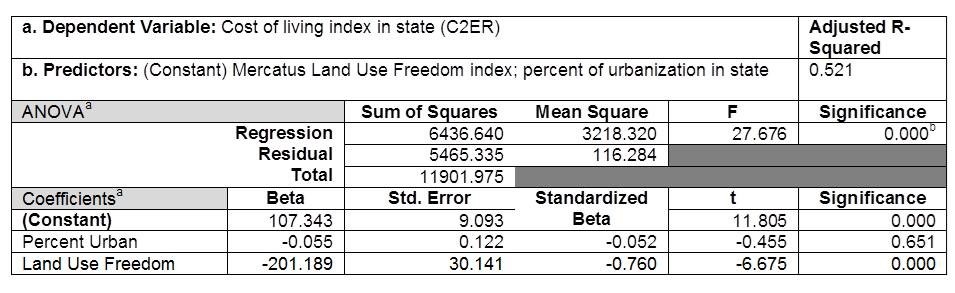

Rognlie’s link between high housing prices and land-use restrictions is buttressed by two studies that focused on California and New York City. To test the proposition that housing costs are driven by land-use regulations and not, say, the degree of urbanization in a state—a common excuse the Left deploys—researchers ran a multivariate regression for all 50 states.

They used the cost of living index from the Council for Community and Economic Research as the dependent variable. The predictors were the degree of urbanization in a state and a state’s land-use freedom score, a component of the Mercatus Center at George Mason University’s Freedom in the 50 States annual survey. The panel below shows the results, indicating that property rights restrictions, not the degree of urbanization, are what drive much of the cost of living.

Liberals Are Making Housing More Expensive

Given liberals’ shining faith in government, it ought to cause a degree of cognitive dissonance if they were to stop and consider that regional land-use planning by highly trained technocrats (a Progressive innovation), local zoning laws, development fees, and, in California, greenhouse-gas emissions, are putting housing out of reach for average workers.

The problem with central planning (always done for our own good, of course) is that most people don’t want to live in crowded conditions. A National Association of Home Builders poll conducted three years ago showed that 71 percent of potential homebuyers wanted a detached home, not a condo or townhouse. In 2009, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that 61.6 percent of the nation’s housing stock was in single-family detached homes, with Iowa having the largest share, at 73.5 percent and New York the lowest, at 41.7 percent.

California, a state ranking as the nation’s second-most-expensive, after Hawaii, was estimated by the Council for Community and Economic Research to have an overall cost of living index of 138.2 in the first quarter of 2015, with its housing component clocking in at 202.8, also the nation’s second-highest.

With California’s late jobs recovery now in full swing, housing prices have rebounded sharply. Cato Institute senior fellow Randal O’Toole says that the greater San Francisco Bay area saw the median home value to median family income ratio hit 6.8 to 1 in 2013, compared to a ratio of 2.2 to 1 in Houston. In 2006, at the peak of the housing bubble, the ratio hit 10 to 1 in San Francisco. It was 2 to 1 in Houston at the time. Once the 2015 data comes, in it will likely show that the prior bubble ratio has been breached.

Housing prices have gotten so out of control in California that O’Toole says, with a bit of hyperbole, “No one can buy anything.” He predicts that average Californians may soon need intergenerational loans or 50-year mortgages to buy a house in job-rich areas. California has the nation’s third-most-restrictive land-use policies, after New Jersey and Maryland.

Forget Tax Credits and Lawsuits

Out of control home price escalation, aided by a constrained supply, has led to another trend: the depopulation of African-Americans from urban areas. O’Toole notes that San Francisco is seeing the nation’s biggest exodus of blacks, in addition to New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Honolulu, and just about every urban area in California. California’s Inland Empire, the Riverside-San Bernardino region, is the sole Golden State exception.

In last month’s decision in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5 to 4 that the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs allocated “…too many tax credits to housing in predominantly black inner-city areas and too few in predominantly white suburban neighborhoods.” This supposedly reinforced “segregated housing patterns.”

That tax credits flowed to where developers wanted to build multi-family housing based on projections of demand should come as no surprise. Many working poor families find it difficult to commute to work from the suburbs to the urban core, given the paucity of mass transit in outlying areas.

Instead of federal tax credits and lawsuits trying to force what the market won’t or can’t do because of zoning and other restrictions, what if property owners were simply allowed to develop their property in a reasonable way?

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has targeted Marin County in California for its lack of minority housing. Marin—liberal, wealthy, and largely white—sits across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco. George Lucas of “Star Wars” fame has lived there for more than 30 years. Lucas wanted to add on to his film studio adjacent to his Marin ranch in 1987. He was blocked by Marin County elected officials on behalf of his neighbors, who didn’t want their slice of paradise spoiled.

In 2012, frustrated by 25 years of stonewalling, Lucas switched plans and lined up a developer to build affordable housing. But local government stalled this project, as well. Now Lucas has decided to fund the 224-unit affordable housing project himself. Construction, if approved, could be completed by 2019—32 years after Lucas wanted to build something on his own land.

Had Marin County officials been of a mind to rebuff homeowners’ demands to infringe on their neighbors’ property rights, Lucas would have had his enlarged studio in 1988 and HUD likely wouldn’t be targeting them for housing discrimination.

Alas, when government spurns liberty to “solve” problems, it creates more problems that need to be “solved.”

Chuck DeVore is vice president of policy at the Texas Public Policy Foundation and served in the California State Assembly from 2004 to 2010.