This commentary originally appeared in Forbes on March 24, 2017.

We have become accustomed to hearing of the financial plight of recent college graduates, a growing number of whom are either unemployed, underemployed, and/or behind on paying their student loans, which today amount cumulatively to roughly $1.3 trillion.

As alarming as this is, it barely begins to tell the full story of how bad things have become in American higher education. How bad? Consider the latest report from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

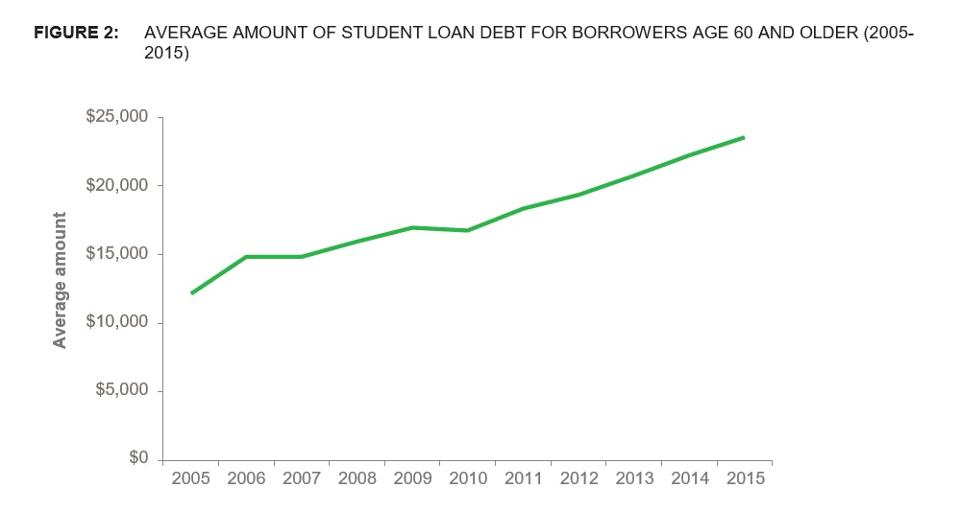

The CFPB report finds that the number of those aged 60 and older “with student loan debt has quadrupled over the last decade in the United States, and the average amount they owe has also dramatically increased.” In 2015, “older consumers owed an estimated $66.7 billion in student loans.” More important, “although most student loan borrowers are young adults between the ages of 18 and 39, consumers age 60 and older are the fastest growing age-segment of the student loan market.” The number of those in this age-group with outstanding student loan debt has increased “from about 700,000 to 2.8 million. During this period, the share of all student loan borrowers that are age 60 and older increased from 2.7 percent to 6.4 percent.” Moreover, “the average amount of student loan debt owed by borrowers age 60 and older roughly doubled from 2005 to 2015, increasing from $12,100 to $23,500” (see graph).

How did those 60 and older—who thought they’d be looking forward to some hard-earned rest during their retirement years—come instead to be the fastest-growing age-group for student loans?

It’s not because they’re hell-bent to return to the hallowed halls of academe. They are not taking out the loans for themselves. The CFPB report finds that “in 2014, 73 percent of student loan borrowers age 60 and older report that their student debt is owed for a child’s and/or grandchild’s education,” whereas “27 percent of student loan borrowers report that their student loan debt is for their own or their spouses’ education.”

Are these older Americans able to bear the increased burden they’ve taken upon themselves in their self-sacrificing quest to help their children and grandchildren? Apparently not. The report reveals that “many older borrowers are behind on their student loan payments.” How far behind? The “proportion of delinquent student loan debt held by borrowers age 60 and older increased from 7.4 percent to 12.5 percent from 2005 to 2012.” In percentage terms, “nearly 40 percent of federal student loan borrowers age 65 and older are in default. Older borrowers who carry student debt later into their lives often struggle to repay or have defaulted on their loans.”

Time, it appears, is not the friend of student-loan borrowers. Quite the contrary. “Borrowers with outstanding loans are increasingly likely to be in default as they age. In 2015, for example, 37 percent of federal student loan borrowers age 65 and older were in default. In comparison, 29 percent of federal student loan borrowers age 50 to 64 were in default, and 17 percent of federal student loan borrowers age 49 and under were in default.” This younger/older disparity likely follows from the fact that those who are younger generally increase their income over the course of their work lives, whereas those who are older generally do not experience a similar magnitude of wage increases after they reach the age of 60.

As dire as the situation has become for older student-loan borrowers, it gets worse: “A growing number of older federal student loan borrowers had their Social Security benefits offset because of unpaid student loans.” Yes, the federal government can “garnish a borrower’s wages and may offset a portion of tax refunds and many government benefits for failing to repay federal student loans.” The number of borrowers 65 and older “who had their Social Security benefits offset to repay a federal student loans increased from about 8,700 to 40,000 borrowers from 2005 to 2015.”

Think about that for a moment. And then reflect on the fact that “social Security benefits are the only source of regular retirement income for 69 percent of beneficiaries age 65 and older” (my emphasis).

Is this what retirement’s “golden years” were supposed to look like?

Still worse, the report finds that a “large portion of older student loan borrowers struggle to afford basic needs.” The data reveal that older Americans with “outstanding student loans are more likely than those without outstanding student loans to report that they have skipped necessary health care needs such as prescription medicines, doctors’ visits, and dental care because they could not afford it.”

This increased burden on older Americans has caused them to tap savings that were being safeguarded for their retirement years. “Among household heads nearing retirement, age 50 to 59, those with outstanding student loan debt have less saved for retirement than their counterparts without student debt.”

The extent of financial damage suffered by older Americans as a result of tuition hyperinflation demonstrates the enormity of the student-loan crisis. The statistics recited above tell us—in case we didn’t already know—that something is rotten in the state of higher education.

The extent of dysfunction of the present system of higher-education finance is such that, in time, it may come to be said that “Only the dead have seen the end of student-loan debt.”